After my research for last week’s blog post on workhouses, I felt that there had to be a bit more to the story, so I continued looking and this led on to law in general. Now that is an absolutely huge subject that I cannot possibly hope to encompass in my blogs, but I can perhaps highlight a few things we have either forgotten or simply were never told about, as the law can be a fascinating insight into the priorities of a particular period in time and quite rightly it is constantly changing. For example, in 1313 MPs were banned from wearing armour or carrying weapons in Parliament, a law which still stands today. Others, such as the monarch’s guards, are still permitted to carry weapons, just not MPs themselves. It’s easy enough to see the chain of events that prompts laws to be written or changed. For example, since around 2013, when driving along a three-lane motorway, rule 264 of the Highway Code states that “You should always drive in the left-hand lane when the road ahead is clear. If you are overtaking a number of slow-moving vehicles, you should return to the left-hand lane as soon as you are safely past.” Middle-lane hogging is when vehicles remain in the middle lane longer than necessary, even when there aren’t any vehicles in the inside lane to overtake. So in a hundred years’ time, this law might be seen as a historical curiosity, although it was heartily welcomed by many drivers. So for rather obvious reasons, some laws are still standing whilst others have been dropped as they are inappropriate in the modern day. But go back to the late 19th century and there were the Locomotive Acts, or Red Flag Acts which were a series of Acts of Parliament which regulated the use of mechanically propelled vehicles on British public highways. The first three, the Locomotives on Highways Act 1861, The Locomotive Act 1865 and Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act 1878, contained restrictive measures on the manning and speed of operation of road vehicles. They also formalised many important road concepts like vehicle registration, registration plates, speed limits, maximum vehicle weight over structures such as bridges, and the organisation of highway authorities. The most draconian restrictions and speed limits were imposed by the 1865 Act, also known as the ‘Red Flag’ Act, which required “all road locomotives, including automobiles, to travel at a maximum of 4mph (6.4km/h) in the country and 2mph (3.2km/h) in the city, as well as requiring a man carrying a red flag to walk in front of road vehicles hauling multiple wagons”. However The 1896 Act removed some restrictions of the 1865 Act and also raised the speed to 14mph (23km/h). But first, let us go back to earlier times. For example, the First Act of Supremacy 1534. Over the course of the 1520s and 1530s, Henry VIII passed a series of laws that changed life in England entirely, and the most significant of these was this First Act of Supremacy which declared that Henry VIII was the Supreme Head of the Church of England instead of the Pope, effectively severing the link between the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church, and providing the cornerstone for the English Reformation. This change was so far-ranging that it is difficult to cover every effect that it had. It meant that England (and ultimately, Britain) would be a Protestant country rather than a Catholic one, with consequences for her allies and her sense of connection to the other countries of Europe. It gave Henry VIII additional licence to continue plundering and shutting down monasteries, which had been huge centres of power in England, with really significant consequences in that their role in alleviating poverty, and providing healthcare and education was lost. It led to centuries of internal and external conflict between the Church of England and other faiths, some of which are still ongoing today. In fact, until 1707, there was no such thing as the United Kingdom. There was England, and there was Scotland, two countries which had shared a monarch since 1603 but which were otherwise legally separate. But by 1707, the situation was becoming increasingly difficult, and union seemed to solve both sides’ fears that they were dangerously exposed to exploitation by the other. England and Scotland had been at each other’s throats since a time before the nations of ‘England’ and ‘Scotland’ even formally existed. The Acts of Union did not bring that to an end right away, but ultimately these ancient enemies became one of the most enduring political unions that has ever existed. That isn’t to say it has gone entirely uncontested as in 2014, a referendum was held on Scottish independence where 55% of voters opted to remain in the union. We should also recall 1807, when the Slave Trade Act was introduced. In fact Britain had played a pivotal role in the international slave trade, though slavery had been illegal in Britain itself since 1102 but with the establishment of British colonies overseas, slaves were used as agricultural labour across the British empire. It was estimated that British ships carried more than three million slaves from Africa to the Americas, second only to the five million slaves which were transported by the Portuguese. The Quakers, or the Religious Society of Friends to give them their proper name, were a nonviolent, pacifist religious movement founded in the mid-17th century who were opposed to slavery from the start of their movement. They pioneered the Abolitionist movement, despite being a marginalised group in their own right. As non-Anglicans, they were not permitted to stand for Parliament. They founded a group to bring non-Quakers on board so as to have greater political influence, as well as working to raise public awareness of the horrors of the slave trade. This was achieved through the publication of books and pamphlets. The effect of the Slave Trade Act, once passed, was rapid. The Royal Navy, which was the leading power at sea at the time, patrolled the coast of West Africa and between 1808 and 1860 freed 150,000 captured slaves. Finally, in 1833, slavery was finally banned throughout the British Empire. In the first few decades of the Industrial Revolution, conditions in British factories were frequently abysmal. 15-hour working days were usual and this included weekends. Apprentices were not supposed to work for more than 12 hours a day, and factory owners were not supposed to employ children under the age of 9, but a parent’s word was considered sufficient to prove a child’s age and even these paltry rules were seldom enforced. Yet the wages that factories offered were still so much better than those available in agricultural labour that there was no shortage of workers willing to put up with these miserable conditions, at least until they had earned enough money to seek out an alternative. It was a similar social movement to the one that had brought an end to slavery that fought child labour in factories, it was also believed that reducing working hours for children would lead to a knock-on effect where working hours for adults would also be reduced. The Factory Act of 1833, among a host of changes, banned children under 9 from working in textile mills, banned children under 18 from working at night, and children between 9 and 13 were not permitted to work unless they had a schoolmaster’s certificate showing they had received two hours’ education per day. So the Factory Act not only improved factory conditions, but also began to pave the way towards education for all. Then, just two years later, a law against cruelty to animals followed. Until 1835, there had been no laws in Britain to prevent cruelty to animals, except one in 1822, which exclusively concerned cattle. Animals were property, and could be treated in whatever way the property-owner wished. It was actually back in 1824 that a group of reformers founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which we know today as the RSPCA. Several of those reformers had also been involved in the abolition of the slave trade, such as the MP William Wilberforce. Their initial focus was on working animals such as pit ponies, which worked in mines, but that soon expanded. The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835, for which the charity’s members lobbied, outlawed bear-baiting and cockfighting, as well as paving the way for further legislation for things such as creating veterinary hospitals, and improving how animals were transported.

Prior to the Married Women’s Property Act 1870, when a woman married a man, she ceased to exist as a separate legal being. All of her property prior to marriage, whether accumulated through wages, inheritance, gifts or anything else became his, and any property she came to possess during marriage was entirely under his control, not hers. There were a handful of exceptions, such as money held in trust, but this option was out of reach of all but the very wealthy. Given the difficulty of seeking a divorce at this time, this effectively meant that a man could do whatever he wished with his wife’s money, including leaving her destitute, and she would have very little legal recourse. But the Act changed this. It gave a woman the right to control money she earned whilst married, as well as keeping inherited property, and made both spouses liable to maintain their children from their separate property, something that was important in relation to custody rights on divorce. The Act was not retrospective, so women who had married and whose property had come into the ownership of their husbands were not given it back, which limited its immediate effect. But ultimately, it was a key stage on the long road to equality between men and women in Britain. It is clear that 1870 was a big year in British politics so fas as education was concerned. This is because before then, the government had provided some funding for schools but this was piecemeal and there were plenty of areas where there were simply no school places to be found. This was complicated by the fact that many schools were run by religious denominations, as there was conflict over whether the government should fund schools run by particular religious groups. As has been seen, under the Factory Act 1833 there were some requirements that children should be educated, but these were frequently ignored. Previously, industrialists had seen education as undesirable, at least when focusing on their ‘bottom line’, as hours when children were in education represented hours when they were not able to work. There were some factory jobs that only children could perform, for instance because of their size. But as automation advanced, it increasingly became the case that a lack of educated workers was holding back industrial production so industrialists became a driving force in pushing through comprehensive education. The Education Act of 1870 didn’t provide free education for all, but it did ensure that schools would be built and funded wherever they were needed, so that no child would miss out on an education simply because they didn’t live near a school. We take it for granted now, but free education for all was not achieved until 1944. At the end of the First World War, the Representation of the People Act 1918 is chiefly remembered as the act that gave women the right to vote, but in fact it went further than that. Only 60% of men in Britain had the right to vote prior to 1918, as voting rights were restricted to men who owned a certain amount of property. Elections had been postponed until the end of the First World War and now, in an atmosphere of revolution, Britain was facing millions of soldiers who had fought for their country returning home and being unable to vote. This was clearly unacceptable. As a result, the law was changed so that men aged over 21, or men who had turned 19 whilst fighting in the First World War, were given the vote. But it was also evident that women had contributed hugely to the war effort, and so they too were given the vote under restricted circumstances. The vote was granted to women over 30 who owned property, were graduates voting in a university constituency or who were either a member or married to a member of the Local Government Register. The belief was that this set of limitations would mean that mostly married women would be voting, and therefore that they would mostly vote the same way as their husbands, so it wouldn’t make too much difference. Women were only granted equal suffrage with men in 1928. Then in 1946 came the National Health Service Act. I personally think that we should be proud of our free health service, especially after I learned what residents of some other countries have to do in order to obtain medical care. In 1942, economist William Beveridge had published a report on how to defeat the five great evils of society, these being squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease. Ignorance, for instance, was to be defeated through the 1944 Education Act, which made education free for all children up to the age of 15. But arguably the most revolutionary outcome of the Beveridge Report was his recommendation to defeat disease through the creation of the National Health Service. This was the principle that healthcare should be free at the point of service, paid for by a system of National Insurance so that everyone paid according to what they could afford. One of the principles behind this was that if healthcare were free, people would take better care of their health, thereby improving the health of the country overall. Or to put it another way, someone with an infectious disease would get it treated for free and then get back to work, rather than hoping it would go away, infecting others and leading to lots of lost working hours. It is an idea that was, and remains, hugely popular with the public.

As I said last week, there had been several new laws with the gradual closure of workhouses and by the beginning of the 20th century some infirmaries were even able to operate as private hospitals. A Royal Commission of 1905 reported that workhouses were unsuited to deal with the different categories of resident they had traditionally housed, and it was recommended that specialised institutions for each class of pauper should be established in which they could be treated appropriately by properly trained staff. The ‘deterrent’ workhouses were in future to be reserved for those considered as incorrigibles, such as drunkards, idlers and tramps. In Britain during the early 1900’s, average life span as considered as about 47 for a man and 50 for a woman. By the end of the century, it was about 75 and 80. Life was also greatly improved by new inventions. In fact, even during the depression of the 1930s things improved for most of the people who had a job. Of course we then had the First World War, where so many people lost their lives. So far as the United Kingdom and the Colonies are concerned, during that war there were about 888,000 military deaths (from all causes) and just about 17,000 civilian deaths due to military action and crimes against humanity. There were also around 1,675,000 military wounded. Then during the Second World War, again just in the United Kingdom (including Crown Colonies) there were almost 384,000 military deaths (from all causes), some 67,200 civilian deaths due to military action and crimes against humanity as well as almost 376,000 military wounded. On 24 January 1918 it was reported in the Daily Telegraph that the Local Government Committee on the Poor Law had presented to the Ministry of Reconstruction a report recommending abolition of the workhouses and transferring their duties to other organisations. That same year, free primary education for all children was provided in the UK. Then a few years later the Local Government Act of 1929 gave local authorities the power to take over workhouse infirmaries as municipal hospitals, although outside London few did so. The workhouse system was officially abolished in the UK by the same Act on 1 April 1930, but many workhouses, renamed Public Assistance Institutions, continued under the control of local county councils. At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 almost 100,000 people were accommodated in the former workhouses, 5,629 of whom were children. Then the 1948 National Assistance Act abolished the last vestiges of the Poor Law, and with it the workhouses. Many of the buildings were converted into retirement homes run by the local authorities, so by 1960 slightly more than half of local authority accommodation for the elderly was provided in former workhouses. Under the Local Government Act 1929, the boards of guardians, who had been the authorities for poor relief since the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, were abolished and their powers transferred to county and county borough councils. The basic responsibilities of the statutory public assistance committees set up under the Act included the provision of both ‘indoor’ and ‘outdoor’ relief. Those unable to work on account of age or infirmity were housed in Public Assistance (formerly Poor Law) Institutions and provided with the necessary medical attention, the committee being empowered to act, in respect of the sick poor, under the terms of the Mental Deficiency Acts 1913-27, the Maternity and Child Welfare Act 1918 and the Blind Persons Act 1920, in a separate capacity from other county council committees set up under those Acts. Outdoor relief for the able-bodied unemployed took the form of ‘transitional payments’ by the Treasury, which were not conditional on previous national insurance contributions, but subject to assessment of need by the Public Assistance Committee. The Unemployment Act 1934 transferred the responsibility for ‘transitional payments’ to a national Unemployment Assistance Board (re-named ‘Assistance Board’ when its scope was widened under the Old Age Pensions and Widows Pensions Act, 1940). Payment was still dependent on a ‘means test’ conducted by visiting government officials and, at the request of the government, East Sussex County Council, in common with other rural counties, agreed that officers of its Public Assistance Department should act in this capacity for the administrative county, excepting the Borough of Hove, for a period of eighteen months after the Act came into effect. Other duties of the Public Assistance Committee included the apprenticing and boarding-out of children under its care, arranging for the emigration of suitable persons, and maintaining a register of all persons in receipt of relief. Under the National Health Service Act 1946, Public Assistance hospitals were then transferred to the new regional hospital boards, and certain personal health services to the new Health Committee. The National Insurance Act 1946 introduced a new system of contributory unemployment insurance, national health insurance and contributory pension schemes, under the control of the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance. Payment of ‘supplementary benefits’ to those not adequately covered by the National Insurance Scheme was made the responsibility of the National Assistance Board under the National Assistance Act 1948 and thus the old Poor Law concept of relief was finally superseded. Under the same Act, responsibility for the residential care of the aged and infirm was laid upon a new statutory committee of the county council, the Welfare Services Committee and the Public Assistance Committee was dissolved. Our world is constantly changing!

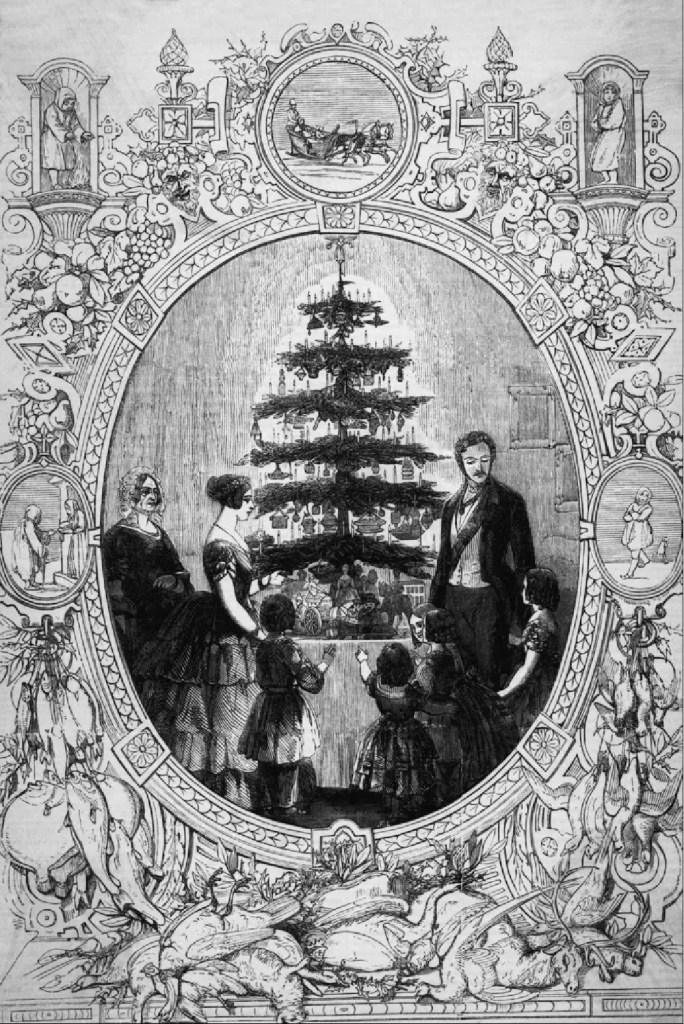

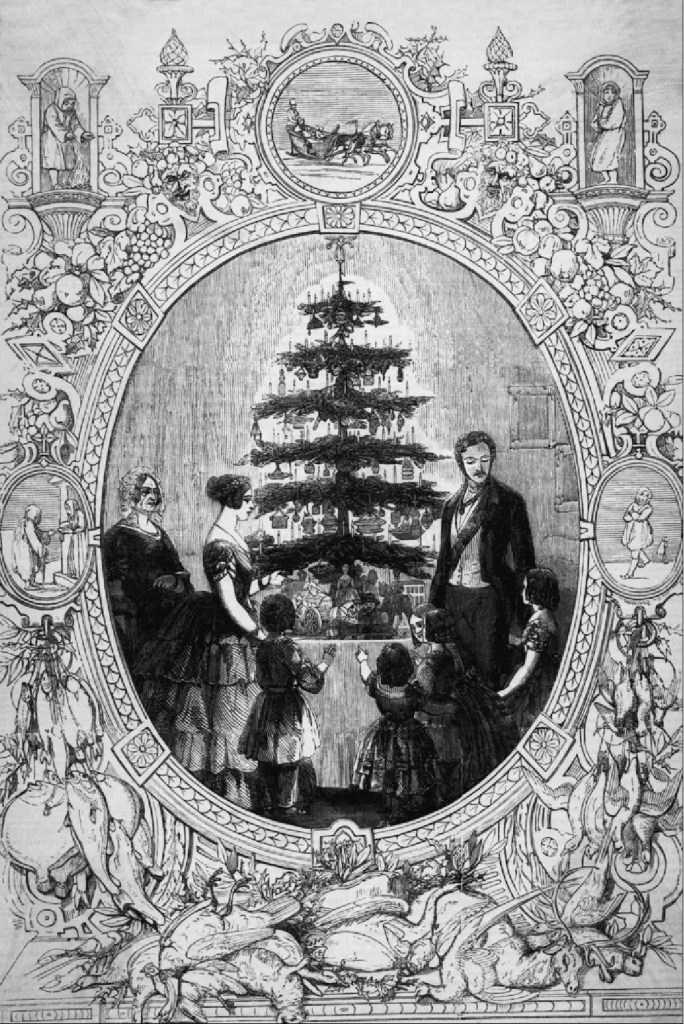

This week, an amusing image for a change…

Click: Return to top of page or Index page