The Sun is the at the centre of the Solar System and is a massive, hot ball of plasma, inflated and heated by nuclear fusion reactions at its core. Part of this internal energy is emitted from the Sun’s surface as light, ultraviolet and infrared radiation, providing most of the energy for life on Earth. The Sun’s radius is about 695,000 kilometres (432,000 miles), or 109 times that of Earth. Its mass is about 330,000 times that of Earth, making up about 99.86% of the total mass of the Solar System. Roughly three-quarters of the Sun’s mass consists of hydrogen (73%); the rest is mostly helium (25%), with much smaller quantities of heavier elements, including oxygen, carbon, neon and iron. The Sun is classed as a G-type main-sequence star, informally called a yellow dwarf, though its light is actually white. It formed approximately 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of matter within a region of a large molecular cloud. Most of this matter gathered in the centre, whereas the rest flattened into an orbiting disk that became the Solar System. The central mass became so hot and dense that it eventually initiated nuclear fusion in its core. It is thought that almost all stars form by this process. Every second, the Sun’s core fuses about 600 million tons of hydrogen into helium, and in the process converts 4 million tons of matter into energy. This energy, which can take between 10,000 and 170,000 years to escape the core, is the source of the Sun’s light and heat. Far in the future, when hydrogen fusion in the Sun’s core diminishes to the point where the Sun is no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium, its core will undergo a marked increase in density and temperature which will push its outer layers to expand, eventually transforming the Sun into a red giant. This process will make the Sun large enough to render Earth uninhabitable approximately five billion years from the present. After this, the Sun will shed its outer layers and become a dense type of cooling star known as a white dwarf, and no longer produce energy by fusion, but still glow and give off heat from its previous fusion. So we have a while yet to live here! The enormous effect of the Sun on Earth has been recognised since prehistoric times and the Sun was thought of by some cultures as a deity. The synodic rotation of Earth and its orbit around the Sun are the basis of some solar calendars and the predominant calendar in use today is the Gregorian, which is based upon the standard sixteenth-century interpretation of the Sun’s observed movement as actual movement.

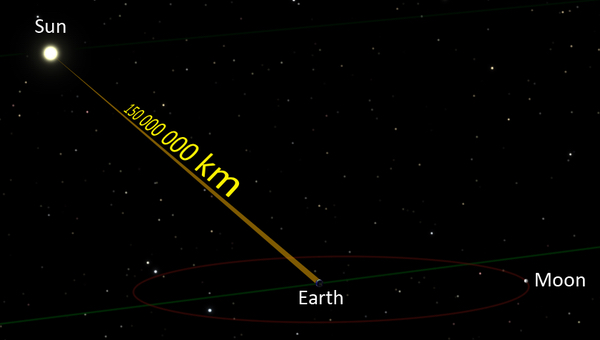

The English word ‘Sun’ developed from Old English ‘sunne’, though it appears in other Germanic languages. This is ultimately related to the word for ‘sun’ in other branches of the Indo-European language family, for example Latin (sōl), ancient Greek, (hēlios) and Welsh (haul), as well as Sanskrit, Persian and others. The principal adjectives for the Sun in English are ‘sunny’ for sunlight and, in technical contexts, ‘solar’ from Latin sol’, the latter found in terms such as solar day, solar eclipse and Solar System. In science fiction, Sol may be used as a name for the Sun to distinguish it from other stars. The English weekday name ‘Sunday’ stems from Old English ‘Sunnandæg’ or “sun’s day”, a Germanic interpretation of the Latin phrase ‘diēs sōlis’, itself a translation of the ancient Greek ‘hēmera hēliou’, or ‘day of the sun’. The Sun makes up about 99.86% of the mass of the Solar System. The Sun has an absolute magnitude of +4.83, estimated to be brighter than about 85% of the stars in the Milky Way, most of which are red dwarfs. The Sun is regarded as a heavy-element-rich, star. The formation of the Sun may have been triggered by shockwaves from one or more nearby supernovae and this is suggested by a high abundance of heavy elements in the Solar System, such as gold and uranium, relative to the abundances of these elements in poorer heavy-element stars. These heavy elements could most plausibly have been produced by nuclear reactions during a supernova, or by transmutation through neutron absorption within a massive, second-generation star. The Sun is by far the brightest object in the Earth’s sky and is about thirteen billion times brighter than the next brightest star, Sirius. At its average distance, light travels from the Sun’s horizon to Earth’s horizon in about eight minutes and twenty seconds, whilst light from the closest points of the Sun and Earth takes about two seconds less. The energy of this sunlight supports almost all life on Earth by photosynthesis and drives both Earth’s climate and weather. The Sun does not have a definite boundary, but its density decreases exponentially with increasing height above the photosphere. For the purpose of measurement, the Sun’s radius is considered to be the distance from its centre to the edge of the photosphere, the apparent visible surface of the Sun and by this measure, the Sun is a near-perfect sphere with an oblateness estimated at nine millionths, which means that its polar diameter differs from its equatorial diameter by only 6.2 miles (10 kilometres). The tidal effect of the planets is weak and does not significantly affect the shape of the Sun. The Sun’s original chemical composition was inherited from the interstellar medium from which it formed. Originally it would have contained about 71.1% hydrogen, 27.4% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements. The hydrogen and most of the helium in the Sun would have been produced by nucleosynthesis in the first twenty minutes of the universe, and the heavier elements were produced by previous generations of stars before the Sun was formed, and spread into the interstellar medium during the final stages of stellar life as well as by events such as supernovae. Since the Sun formed, the main fusion process has involved fusing hydrogen into helium and over the past 4.6 billion years, the amount of helium and its location within the Sun has gradually changed. Within the core, the proportion of helium has increased from about 24% to about 60% due to fusion, and some of the helium and heavy elements have settled from the photosphere towards the centre of the Sun because of gravity, but the proportions of heavier elements are unchanged. Heat is transferred outward from the Sun’s core by radiation rather than by convection, so the fusion products are not lifted outward by heat; they remain in the core and gradually an inner core of helium has begun to form that cannot be fused because presently the Sun’s core is not hot or dense enough to fuse helium. In the current photosphere, the helium fraction is reduced, and the metallicity is only 84% of what it was in the ‘protostellar’ phase, that is before nuclear fusion in the core started. In the future, helium will continue to accumulate in the core, and in about 5 billion years this gradual build-up will eventually become a red giant.

The visible surface of the Sun, the photosphere, is the layer below which the Sun becomes opaque to visible light. Photons produced in this layer escape the Sun through the transparent solar atmosphere above it and become solar radiation, sunlight. The change in opacity is due to the decreasing amount of ‘H−ions’, which absorb visible light easily. Conversely, the visible light we see is produced as electrons react with hydrogen atoms to produce H-ions. The photosphere is up to hundreds of kilometres thick, and is slightly less opaque than air on Earth. Because the upper part of the photosphere is cooler than the lower part, an image of the Sun appears brighter in the centre than on the edge or limb of the solar disk, in a phenomenon known as limb darkening. During early studies of the optical spectrum of the photosphere, some absorption lines were found that did not correspond to any chemical elements then known on Earth. In 1868, Norman Lockyer hypothesised that these absorption lines were caused by a new element that he dubbed helium, after the Greek Sun god Helios. Twenty-five years later, helium was isolated on Earth. The Sun’s atmosphere is composed of four parts, these being the photosphere (visible under normal conditions), the chromosphere, the transition region, the corona and the heliosphere. During a total solar eclipse, the photosphere is blocked, making the corona visible. The coolest layer of the Sun is a temperature minimum region extending to about 500 km above the photosphere, and has a temperature of about 4,100K. This part of the Sun is cool enough to allow for the existence of simple molecules such as carbon monoxide and water, which can be detected via their absorption spectra. The chromosphere, transition region, and corona are much hotter than the surface of the Sun.

Above the temperature minimum layer is a layer about 2,000 km thick, dominated by a spectrum of emission and absorption lines. It is called the chromosphere from the Greek root ‘chroma’, meaning colour, because the chromosphere is visible as a coloured flash at the beginning and end of total solar eclipses. The temperature of the chromosphere increases gradually with altitude, ranging up to around 20,000K near the top. In the upper part of the chromosphere helium becomes partially ionised. Above the chromosphere, in a thin (about 200 km) transition region, the temperature rises rapidly from around 20,000K in the upper chromosphere to coronal temperatures closer to 1,000,000K. The temperature increase is facilitated by the full ionisation of helium in the transition region, which significantly reduces radiative cooling of the plasma. The transition region does not occur at a well-defined altitude, rather it forms a kind of ‘nimbus’ around chromospheric features such as spicules and filaments and is in constant, chaotic motion. The transition region is not easily visible from Earth’s surface, but is readily observable from space by instruments sensitive to the ultraviolet portion of the spectrum.

The corona is the next layer of the Sun and the average temperature of this corona and solar wind is about 1,000,000 to 2,000,000K, however in the hottest regions it is 8,000,000 to 20,000,000K. Although no complete theory yet exists to account for the temperature of the corona, at least some of its heat is known to be from ‘magnetic reconnection’, a physical process occurring in electrically conducting plasmas in which the magnetic topology is rearranged and magnetic energy is converted to kinetic energy, thermal energy and particle acceleration. The corona is the extended atmosphere of the Sun, which has a volume much larger than the volume enclosed by the Sun’s photosphere. A flow of plasma outward from the Sun into interplanetary space is the solar wind. Meanwhile the heliosphere, the tenuous outermost atmosphere of the Sun, is filled with solar wind plasma. This outermost layer of the Sun is defined to begin at the distance where the flow of the solar wind becomes ‘superalfvénic’, that is, where the flow becomes faster than the speed of Alfvén waves, at approximately 20 solar radii (0.1 AU). Turbulence and dynamic forces in the heliosphere cannot affect the shape of the solar corona within, because the information can only travel at the speed of Alfvén waves. The solar wind travels outward continuously through the heliosphere, forming the solar magnetic field into a spiral shape until it impacts the ‘heliopause’ more than 50 Astronomical Units (AU) from the Sun. In December 2004, the Voyager 1 probe passed through a shock front that is thought to be part of the heliopause. In late 2012, Voyager 1 recorded a marked increase in cosmic ray collisions and a sharp drop in lower energy particles from the solar wind, which suggested that the probe had passed through the heliopause and entered the interstellar medium and indeed did so August 25, 2012 at approximately 122 AU from the Sun. The heliosphere has a heliotail which stretches out behind it due to the Sun’s movement. The Sun emits light across the visible spectrum, so its colour is white when viewed from space or when the Sun is high in the sky. The Solar radiance per wavelength peaks in the green portion of the spectrum when viewed from space. When the Sun is very low in the sky, atmospheric scattering renders the Sun yellow, red, orange, or magenta, and in rare occasions even green or blue. Despite its typical whiteness, some cultures mentally picture the Sun as yellow and some even red; the reasons for this are cultural and exact ones are the subject of debate. The Sun is classed as a G2V star, with ‘G2’ indicating its surface temperature of approximately 5,778 K (5,505 °C; 9,941 °F), and V that it, like most stars, is a ‘main-sequence’ star.

The Solar Constant is the amount of power that the Sun deposits per unit area that is directly exposed to sunlight. It is equal to approximately 1,368 watts per square metre at a distance of one astronomical unit (AU) from the Sun (that is, on or near Earth). Sunlight on the surface of Earth is attenuated by Earth’s atmosphere, so that less power arrives at the surface in clear conditions when the Sun is near the zenith. Sunlight at the top of Earth’s atmosphere is composed (by total energy) of about 50% infrared light, 40% visible light, and 10% ultraviolet light and the atmosphere in particular filters out over 70% of solar ultraviolet, especially at the shorter wavelengths. Solar ultraviolet radiation ionises Earth’s dayside upper atmosphere, creating the electrically conducting ionosphere. Ultraviolet light from the Sun has antiseptic properties and can be used to sanitise tools and water. It also causes sunburn and has other biological effects such as the production of vitamin D and sun tanning. It is also the main cause of skin cancer. Ultraviolet light is strongly attenuated by Earth’s ozone layer, so that the amount of UV varies greatly with latitude and has been partially responsible for many biological adaptations, including variations in human skin colour in different regions of the Earth.

The Sun is about half-way through its main-sequence stage, during which nuclear fusion reactions in its core fuse hydrogen into helium. Each second, more than four million tonnes of matter are converted into energy within the Sun’s core, producing neutrinos and solar radiation. At this rate, the Sun has so far converted around 100 times the mass of Earth into energy, about 0.03% of the total mass of the Sun. It is gradually becoming hotter in its core, hotter at the surface, larger in radius, and more luminous during its time on the main sequence. Since the beginning of its main sequence life, it has expanded in radius by 15% and the surface has increased in temperature from 5,620 K (5,350 °C; 9,660 °F) to 5,777 K (5,504 °C; 9,939 °F), resulting in a 48% increase in luminosity from 0.677 solar luminosities to its present-day 1.0 solar luminosity. This occurs because the helium atoms in the core have a higher mean molecular weight than the hydrogen atoms which were fused, resulting in less thermal pressure. The core is therefore shrinking, allowing the outer layers of the Sun to move closer to the centre, releasing gravitational potential energy. It is believed that half of this released gravitational energy goes into heating, which leads to a gradual increase in the rate at which fusion occurs and thus an increase in the luminosity. This process speeds up as the core gradually becomes denser and at present, it is increasing in brightness by about 1% every 100 million years. It will take at least one billion years from now to deplete liquid water from the Earth from such increase. After that, the Earth will cease to be able to support complex, multicellular life and the last remaining multi-cellular organisms on the planet will suffer a final, complete mass extinction. Also, according to the ESA’s Gaia space observatory mission made in 2022, the sun will be at its hottest point at the eight billion year mark, but will spend a total of approximately ten to eleven billion years as a main-sequence star before its Red Giant phase.

But the Sun does not have enough mass to explode as a supernova. Instead, when it runs out of hydrogen in the core in approximately five billion years, core hydrogen fusion will stop, and there will be nothing to prevent the core from contracting. The release of gravitational potential energy will cause the luminosity of the Sun to increase, ending the main sequence phase and leading the Sun to expand over the next billion years: first into a subgiant and then into a red giant. The heating due to gravitational contraction will also lead to expansion of the Sun and hydrogen fusion in a shell just outside the core, where unfused hydrogen remains, contributing to the increased luminosity, which will eventually reach more than 1,000 times its present luminosity. When the Sun enters its red-giant branch phase, it will engulf Mercury and most likely Venus, reaching about 0.75 AU (110 million km; 70 million miles). The Sun will spend around a billion years in this phase and lose around a third of its mass. After the red-giant branch, the Sun has approximately 120 million years of active life left, but much happens. First, the core (full of degenerate helium) will ignite violently in the helium flash and it is estimated that 6% of the core, itself 40% of the Sun’s mass, will be converted into carbon within a matter of minutes. The Sun then shrinks to around ten times its current size and fifty times the luminosity, with a temperature a little lower than today. It will then have reached the ‘horizontal branch’, but a star of the Sun’s metallicity does not evolve along the horizontal branch. Instead, it just becomes moderately larger and more luminous over about 100 million years as it continues to react helium in the core. When the helium is exhausted, the Sun will repeat the expansion it followed when the hydrogen in the core was exhausted. This time, however, it all happens faster, and the Sun becomes larger and more luminous, engulfing Venus if it has not already. This is the giant-branch phase, and the Sun is alternately reacting hydrogen in a shell or helium in a deeper shell. After about 20 million years on the early asymptotic giant branch, the Sun becomes increasingly unstable, with rapid mass loss and thermal pulses that increase the size and luminosity for a few hundred years every 100,000 years or so. The thermal pulses become larger each time, with the later pulses pushing the luminosity to as much as 5,000 times the current level and the radius to over 1 AU (150 million km; 93 million miles). According to a 2008 model, Earth’s orbit will have initially expanded to at most 1.5 AU (220 million km; 140 million miles) due to the Sun’s loss of mass as a red giant. However, Earth’s orbit will later start shrinking due to tidal forces and, eventually, drag from the lower chromosphere so that it is engulfed by the Sun during the tip of the red-giant branch phase, some 3.8 and 1 million years after Mercury and Venus have respectively suffered the same fate. Models vary depending on the rate and timing of mass loss. Models that have higher mass loss on the red-giant branch produce smaller, less luminous stars at the tip of the asymptotic giant branch, perhaps only 2,000 times the luminosity and less than 200 times the radius. For the Sun, four thermal pulses are predicted before it completely loses its outer envelope and starts to make a planetary nebula. By the end of that phase, which will last approximately 500,000 years, the Sun will only have about half of its current mass.The post-giant-branch evolution is even faster. The luminosity stays approximately constant as the temperature increases, with the ejected half of the Sun’s mass becoming ionised into a planetary nebula as the exposed core reaches 30,000 K (29,700 °C; 53,500 °F). The final naked core, a white dwarf, will have a temperature of over 100,000 K (100,000 °C; 180,000 °F), and contain an estimated 54.05% of the Sun’s present-day mass. The planetary nebula will disperse in about 10,000 years, but the white dwarf will survive for trillions of years before fading to a hypothetical black dwarf. I think that is enough for now! In the future I plan to write about the Solar System and the planets, which I hope you will find of interest.

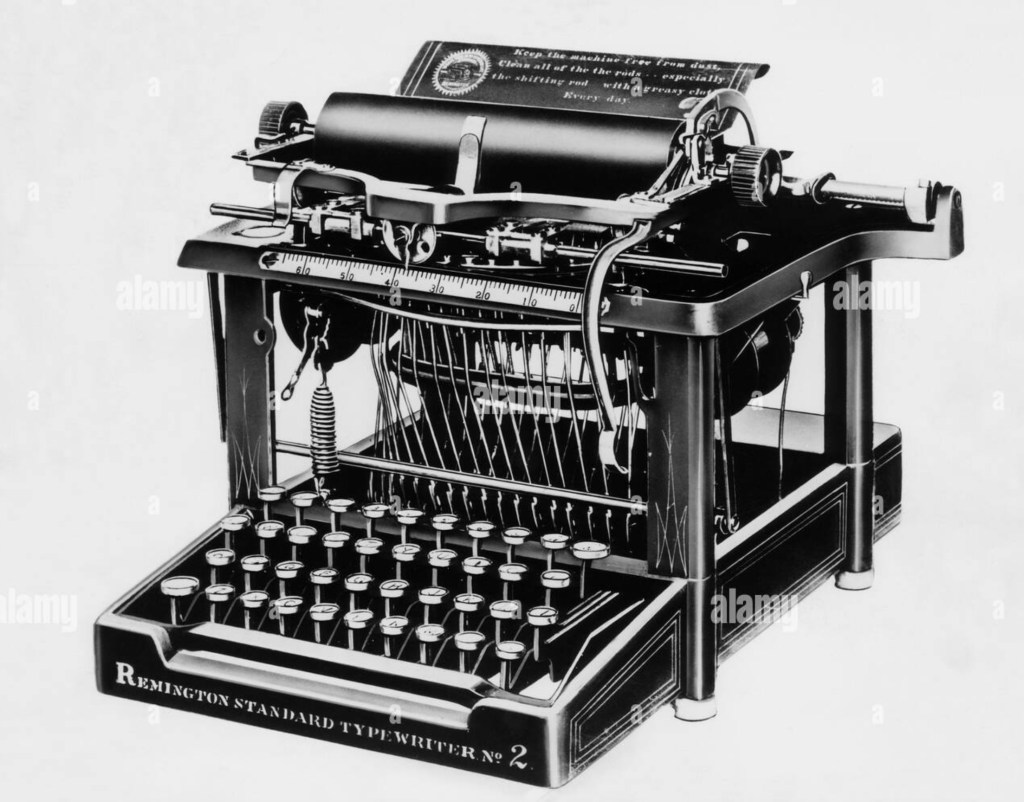

This week…Time

People, especially children, don’t know what they don’t know, so raising awareness is a vital first step in their education process. For example, first becoming aware that ‘time’ exists, leading on to using a clock to measure and display time.

Click: Return to top of page or Index page