The Western Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall and in Islam as the Buraq Wall is a portion of ancient limestone wall in the Old City of Jerusalem that forms part of the larger retaining wall of the hill known to both Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount. Just over half the wall’s total height, including its seventeen courses (continuous horizontal layers of similarly sized building material) located below street level, dates from the end of the Second Temple period, and is believed to have been begun by Herod the Great. The very large stone blocks of the lower courses are Herodian, the courses of medium-sized stones above them were added during the Umayyad period (661–750), whilst the small stones of the uppermost courses are of more recent date, especially from the Ottoman period. The Western Wall plays an important role in Judaism due to its proximity to the Temple Mount. Because of the Temple Mount entry restrictions, the Wall is the holiest place where Jews are permitted to pray outside the previous Temple Mount platform, as the presumed site of the Holy of Holies, the most sacred site in the Jewish faith, lies just behind it. The original, natural, and irregular-shaped Temple Mount was gradually extended to allow for an ever-larger Temple compound to be built at its top. The earliest source mentioning this specific site as a place of Jewish worship is from the seventeenth century. The term Western Wall and its variations are mostly used in a narrow sense for the section of the wall used for Jewish prayer and called the “Wailing Wall”, referring to the practice of Jews weeping at the site. During the period of Christian Roman rule over Jerusalem (c. 324–638), Jews were completely barred from Jerusalem except on Tisha B’Av, the day of national mourning for the Temples. The term “Wailing Wall” has historically been used mainly by Christians, with religious Jews generally considering it derogatory. In a broader sense, “Western Wall” can refer to the entire 488-metre-long (1,601ft) retaining wall on the western side of the Temple Mount. The classic portion now faces a large plaza in the Jewish Quarter, near the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, whilst the rest of the wall is concealed behind structures in the Muslim Quarter with the small exception of an 8-metre (26ft) section, the so-called Little Western Wall or ‘Small Wailing Wall’. This segment of the western retaining wall derives particular importance from never been fully obscured by medieval buildings, and displaying much of the original Herodian stonework. In religious terms, the ‘Little Western Wall’ is presumed to be even closer to the Holy of Holies and thus to the ‘Presence of God’, and the underground Warren’s Gate, which was out of reach for Jews from the twelfth century until its partial excavation in the twentieth century. Whilst the wall was considered an integral part of the property of the Moroccan Quarter under Muslim rule, a right of Jewish prayer and pilgrimage has long existed as part of a ‘status quo’ between the two states. This position was confirmed in a 1930 international commission during the British Mandate period. With the rise of the Zionist movement in the early twentieth century, the wall became a source of friction between the Jewish and Muslim communities, the latter being worried that the wall could be used to further Jewish claims to the Temple Mount and thus Jerusalem. During this period outbreaks of violence at the foot of the wall became commonplace, with a particularly deadly riot in 1929 in which 133 Jews and 116 Arabs were killed, with many more people injured. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the eastern portion of Jerusalem was occupied by Jordan and under Jordanian control Jews were completely expelled from the Old City including the Jewish Quarter. Jews were also barred from entering the Old City for nineteen years, effectively banning Jewish prayer at the site of the Western Wall. This period ended on June 10, 1967, when Israel gained control of the site following the Six-Day War. Three days after establishing control over the Western Wall site, the Moroccan Quarter was bulldozed by Israeli authorities to create space for what is now the Western Wall plaza.

The term Western Wall commonly refers to a 187-foot (57m) exposed section of a much longer retaining wall, built by Herod on the western flank of the Temple Mount. Only when used in this sense is it synonymous with the term Wailing Wall. This section faces a large plaza and is set aside for prayer. In its entirety, the western retaining wall of the Herodian Temple Mount complex stretches for 1,600 feet (488m), most of which is hidden behind medieval residential structures built along its length. There are only two other revealed sections: the southern part of the Wall which measures approximately 262 feet (80m) and is separated from the prayer area by just a narrow stretch of archaeological remains and another, much shorter section, the Little Western Wall, which is located close to the Iron Gate. The entire western wall functions as a retaining wall, supporting and enclosing the ample substructures built by Herod the Great around nineteen BC. Herod’s project was to create an artificial extension to the small quasi-natural plateau on which the First Temple stood, finally transforming it into the almost rectangular, wide expanse of the Temple Mount platform visible today.

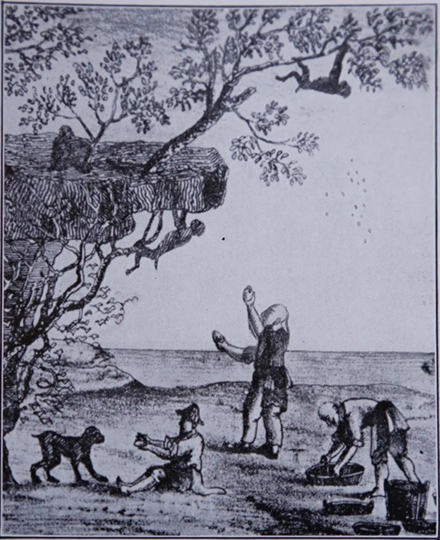

According to the Hebrew Bible, Solomon’s Temple was built atop what is known as the Temple Mount in the tenth century BC and destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC and the Second Temple completed and dedicated in 516 BC. Then around 19 BC Herod the Great began a massive expansion project on the Temple Mount. In addition to fully rebuilding and enlarging the Temple, he artificially expanded the platform on which it stood, doubling it in size. Today’s Western Wall formed part of the retaining perimeter wall of this platform. In 2011, Israeli archaeologists announced the surprising discovery of Roman coins minted well after Herod’s death, found under the foundation stones of the wall. The excavators came upon the coins inside a ritual bath that predates Herod’s building project, which was filled in to create an even base for the wall and was located under its southern section. This seems to indicate that Herod did not finish building the entire wall by the time of his death in 4 BC. The find also confirms the description by a historian which states that construction was finished only during the reign of King Agrippa II, Herod’s great-grandson. Given this information, the surprise mainly regarded the fact that an unfinished retaining wall in this area could also mean that at least parts of the splendid Royal Stoa and the monumental staircase leading up to it could not have been completed during Herod’s lifetime. Also surprising was the fact that the usually very thorough Herodian builders had cut corners by filling in the ritual bath, rather than placing the foundation course directly onto the much firmer bedrock. Some scholars are doubtful of the interpretation and have offered alternative explanations, such as, for example, later repair work. Herod’s Temple was destroyed by the Romans, along with the rest of Jerusalem, in 70 AD during the First Jewish–Roman War. During much of the second to fifth centuries, after the Roman defeat of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 AD, Jews were banned from Jerusalem. There is some evidence that Roman emperors in the second and third centuries did permit them to visit the city to worship on the Mount of Olives and sometimes on the Temple Mount itself. When the empire started becoming Christian under Constantine I they were given permission to enter the city once a year, on the ‘Tisha B’Av’, to lament the loss of the Temple at the wall. In the fourth century, Christian sources reveal that the Jews encountered great difficulty in buying the right to pray near the Western Wall, at least on the ninth of Av. In 425 AD, the Jews of the Galilee wrote to the Byzantine empress seeking permission to pray by the ruins of the Temple. Permission was granted and they were officially permitted to resettle in Jerusalem.

In 1517, the Turkish Ottomans conquered Jerusalem from the Mamluks who had held it since 1250. Selim’s son, Suleiman the Magnificent, ordered the construction of an imposing wall to be built around the entire city, which still stands today. Some folklore relates to Suleiman’s quest to locate the Temple site and his order to have the area “swept and sprinkled, and the Western Wall washed with rosewater” upon its discovery. At the time, Jews received official permission to worship at the site and an Ottoman architect built an oratory for them there. Over the centuries, land close to the Wall became built up. Public access to the Wall was through the Moroccan Quarter, a labyrinth of narrow alleyways. In May 1840 a ‘firman’ or royal decree forbade the Jews to pave the passageway in front of the Wall. It also cautioned them against “raising their voices and displaying their books there.” They were, however, allowed “to pay visits to it as of old”. Over time the increased numbers of people gathering at the site resulted in tensions between the Jewish visitors who wanted easier access and more space, and the residents, who complained of the noise. This gave rise to Jewish attempts at gaining ownership of the land adjacent to the Wall. In 1895 there was a failed effort to purchase the Western Wall and the attempts of the Palestine Land Development Company to purchase the environs of the Western Wall for the Jews just before the outbreak of World War I also never came to fruition. In the first two months following the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the First World War, the Turkish governor of Jerusalem offered to sell the Moroccan Quarter, which consisted of about twenty-five houses, to the Jews in order to enlarge the area available to them for prayer. He requested a sum of £20,000 which would be used to both rehouse the Muslim families and to create a public garden in front of the Wall. However, the Jews of the city lacked the necessary funds. A few months later, under Muslim Arab pressure on the Turkish authorities in Jerusalem, Jews became forbidden by official decree to place benches and light candles at the Wall. This sour turn in relations was taken up by the Chief Rabbi at the time who managed to get the ban overturned. In 1915 it was reported that the wall was closed off ‘as a sanitary measure’.

In December 1917, Allied forces captured Jerusalem from the Turks. It was pledged “that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred”. In 1919 the Zionist leader approached the British Military Governor of Jerusalem and offered between £75,000 and £100,000 (approx. £5m in modern terms) to purchase the area at the foot of the Wall and rehouse the occupants. The Governor was enthusiastic about the idea because he hoped some of the money would be used to improve Muslim education. Although they appeared promising at first, negotiations broke down after strong Muslim opposition. In early 1920, the first Jewish-Arab dispute over the Wall occurred when the Muslim authorities were carrying out minor repair works to the Wall’s upper courses. The Jews, whilst agreeing that the works were necessary, appealed to the British that they be made under supervision of the newly formed Department of Antiquities, because the Wall was an ancient relic. In 1926 an effort was made to lease the Maghrebi, which included the wall, with the plan of eventually buying it. Negotiations were begun in secret by a Jewish judge, with financial backing from an American millionaire. The chairman of the Palestine Zionist Executive explained that the aim was “quietly to evacuate the Moroccan occupants of those houses which it would later be necessary to demolish” to create an open space with seats for aged worshippers to sit on. However, the price became excessive and the plan came to nothing. The Va’ad Leumi, against the advice of the Palestine Zionist Executive, demanded that the British expropriate the wall and give it to the Jews, but the British refused. In 1922, an agreement issued by the mandatory authority forbade the placing of benches or chairs near the Wall. The last occurrence of such a ban was in 1915, but the Ottoman decree was soon retracted. In 1928 the District Commissioner of Jerusalem acceded to an Arab request to implement the ban. This led to a British officer being stationed at the Wall making sure that Jews were prevented from sitting. Nor were Jews permitted to separate the sexes with a screen. In practice, a flexible modus vivendi had emerged and such screens had been put up from time to time when large numbers of people gathered to pray. From October 1928 onward, a Mufti organised a series of measures to demonstrate the Arabs’ exclusive claims to the Temple Mount and its environs. He ordered new construction next to and above the Western Wall. The British granted the Arabs permission to convert a building adjoining the Wall into a mosque and to add a minaret. A muezzin (the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer) was appointed to perform the Islamic call to prayer and Sufi rites directly next to the Wall. These were seen as a provocation by the Jews who prayed at the Wall. The Jews protested and tensions increased.

In the summer of 1929, the Mufti ordered an opening be made at the southern end of the alleyway which straddled the Wall. The former cul-de-sac became a thoroughfare which led from the Temple Mount into the prayer area at the Wall. Mules were herded through the narrow alley, often dropping excrement. This, together with other construction projects in the vicinity, and restricted access to the Wall, resulted in Jewish protests to the British, who remained indifferent.

On August 14, 1929, after attacks on individual Jews praying at the Wall, 6,000 Jews demonstrated in Tel Aviv, shouting “The Wall is ours.” The next day, the Jewish fast of Tisha B’Av, three hundred youths raised the Zionist flag and sang ‘Hatikva’, the national anthem of the state of Israel, at the Wall. The day after, on August 16, an organised mob of two thousand Muslim Arabs descended on the Western Wall, injuring the beadle and burning prayer books, liturgical fixtures and notes of supplication. The rioting spread to the Jewish commercial area of town, and was followed a few days later by the Hebron massacre. One hundred and thirty-three Jews were killed with many more injured in the Arab riots. This was by far the deadliest attack on Jews during the period of British Rule over Palestine. In 1930, in response to the 1929 riots, the British Government appointed a commission “to determine the rights and claims of Muslims and Jews in connection with the Western or Wailing Wall”, and to determine the causes of the violence and prevent it in the future. The League of Nations approved the commission on condition that the members were not British.

The Commission concluded that the wall, and the adjacent pavement and Moroccan Quarter, were solely owned by the Muslim ‘waqf’, a Jordanian-appointed organisation responsible for controlling and managing the Islamic edifices on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, though Jews had the right to “free access to the Western Wall for the purpose of devotions at all times”, subject to some stipulations that limited which objects could be brought to the Wall and forbade the blowing of the shofar, an ancient musical horn (typically made of a ram’s horn), which was made illegal. Muslims were also forbidden to disrupt Jewish devotions by driving animals or other means. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War the Old City together with the Wall was controlled by Jordan. Neither Israeli Arabs nor Israeli Jews could visit their holy places in the Jordanian territories, though an exception was made for Christians to participate in Christmas ceremonies in Bethlehem. Some sources claim Jews could only visit the wall if they travelled through Jordan (which was not an option for Israelis) and did not have an Israeli visa stamped in their passports. Only Jordanian soldiers and tourists were to be found there. A vantage point on Mount Zion, from which the Wall could be viewed, became the place where Jews gathered to pray. For thousands of pilgrims, the Mount, being the closest location to the Wall under Israeli control, became a substitute site for the traditional priestly blessing ceremony which takes place on the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. During the Jordanian rule of the Old City, a ceramic street sign in Arabic and English was affixed to the stones of the ancient wall. It was made up of eight separate ceramic tiles and said ‘Al Buraq Road’ in Arabic at the top with the English “Al-Buraq (Wailing Wall) Rd” below. When Israeli soldiers arrived at the wall in June 1967, one attempted to scrawl Hebrew lettering on it. The Jerusalem Post reported that on June 8, Ben-Gurion went to the wall and “looked with distaste” at the road sign, saying “this is not right, it should come down” and he proceeded to dismantle it. This act signalled the climax of the capture of the Old City and the ability of Jews to once again access their holiest sites. Emotional recollections of this event were related by David Ben-Gurion and Shimon Peres.

Following Israel’s victory during the 1967 Six-Day War, the Western Wall came under Israeli control. Forty-eight hours after capturing the wall, the military, without explicit government order, hastily proceeded to demolish the entire Moroccan Quarter. The narrow pavement, which could accommodate a maximum of 12,000 people per day, was transformed into an enormous plaza that could hold in excess of 400,000. Several months later, the pavement close to the wall was excavated to a depth of two and half metres, exposing an additional two courses of large stones. The section of the wall dedicated to prayers was thus extended southwards to double its original length. The narrow, pre-1948 alley along the wall, used for Jewish prayer, was enlarged with the entire Western Wall Plaza covering 20,000 square metres (4.9 acres), stretching from the wall to the Jewish Quarter.

In 2005, the Western Wall Heritage Foundation initiated a major renovation effort under the then Rabbi-of-the-Wall. Its goal was to renovate and restructure the area within Wilson’s Arch, the covered area to the left of worshipers facing the Wall in the open prayer plaza, in order to increase access for visitors and for prayer. On July 25, 2010, a ‘ner tamid’, an oil-burning ‘eternal light’ was installed within the prayer hall within Wilson’s Arch, the first eternal light installed in the area of the Western Wall. According to the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, requests had been made for many years that an olive oil lamp be placed in the prayer hall of the Western Wall Plaza, as is the custom in Jewish synagogues, to represent the menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem as well as the continuously burning fire on the altar of burnt offerings in front of the Temple, especially in the closest place to those ancient flames.

A number of special worship events have been held since the renovation. They have taken advantage of the cover, temperature control, and enhanced security. However, in addition to the more recent programmes, one event occurred in September 1983, even before the modern renovation. At that time U.S. Sixth Fleet Chaplain, Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff was allowed to hold the first interfaith service ever conducted at the Wall during the time it was under Israeli control, and that included men and women sitting together. The ten-minute service included the Priestly Blessing recited by Resnicoff, who is a Kohen (priest). A Ministry of Religions representative was present, responding to press queries that the service was authorised as part of a special welcome for the U.S. Sixth Fleet. Many contemporary Orthodox scholars rule that the area in front of the Wall has the status of a synagogue and must be treated with due respect, and this is the view upheld by the authority in charge of the wall. As such, men and married women are expected to cover their heads upon approaching the Wall, and to dress appropriately. When departing, the custom is to walk backwards away from the Wall to show its sanctity. On Saturdays, it is forbidden to enter the area with electronic devices, including cameras, which infringe on the sanctity of the Sabbath. Some Orthodox Jewish codifiers warn against inserting fingers into the cracks of the Wall as they believe that the breadth of the Wall constitutes part of the Temple Mount itself and retains holiness, whilst others who permit doing so claim that the Wall is located outside the Temple area. In the past, some visitors would write their names on the Wall, or based upon various scriptural verses, would drive nails into the crevices. These practices stopped after rabbis determined that such actions compromised the sanctity of the Wall. Another practice also existed whereby pilgrims or those intending to travel abroad would hack off a chip from the Wall or take some of the sand from between its cracks as a good luck charm or memento. In the late nineteenth century the question was raised as to whether this was permitted and a long ‘responsa’, the term used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars in historic religious law, appeared in the Jerusalem newspaper Havatzelet in 1898. It concluded that even if according to Jewish Law it was permitted, the practices should be stopped as it constituted a desecration. More recently a ruling was given that it is forbidden to remove small chips of stone or dust from the Wall, although it is permissible to take twigs from the vegetation which grows in the Wall for an amulet, as they contain no holiness. Cleaning the stones is also problematic, as sadly blasphemous graffiti once sprayed by a tourist was left visible for months until it began to peel away.

There was once an old custom of removing one’s shoes upon approaching the Wall. A seventeenth-century collection of special prayers to be said at holy places mentions that “upon coming to the Western Wall one should remove his shoes, bow and recite…”. Over the years the custom of standing barefoot at the Wall has ceased, as there is no need to remove one’s shoes when standing by the Wall, because the plaza area is outside the sanctified precinct of the Temple Mount. According to Jewish Law, one is obliged to grieve and rend one’s garment upon visiting the Western Wall and seeing the desolate site of the Temple.

Although during the late nineteenth century no formal segregation of men and women was to be found at the Wall, conflict erupted in July 1968 when members of the World Union for Progressive Judaism were denied the right to host a mixed-gender service at the site after the Ministry of Religious Affairs insisted on maintaining the gender segregation customary at Orthodox places of worship. The progressives responded by claiming that “the Wall is a shrine of all Jews, not one particular branch of Judaism.” In 1988, the small but vocal group called Women of the Wall launched a campaign for recognition of non-Orthodox prayer at the Wall. Their form and manner of prayer elicited a violent response from some Orthodox worshippers and they were subsequently banned from holding services at the site. But in 1989 the Women of the Wall petitioned to secure the right of women to pray at the wall without restrictions. Quite a story, but I hope you’ve found it interesting.

This week… a quote I am reminded of.

“Change is the essential process of all existence.”

~ Spock, Star Trek.

Click: Return to top of page or Index page