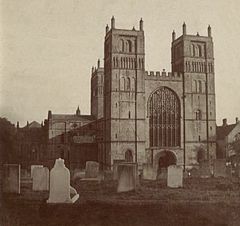

Some years ago, whilst still living in Peterborough, I was privileged to join a small choir which, as well as performing concerts locally, also travelled to a few different cathedrals where we “stood in” for the resident choirs. So I got to sing in some really lovely places with a great group of people. We were small in number, at most about a dozen and it was hard work at times, but we all enjoyed it. One such place was Southwell Minster, which is both a minster and cathedral in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. It is situated six miles (9.7 km) from Newark-on-Trent and thirteen miles (21 km) from Mansfield. It is the seat of the Bishop of Southwell and Nottingham as well as the Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham. It is a grade I listed building. Much of the main fabric is ‘Romanesque’, or Norman in traditional English terminology but the Minster is most famous for the Gothic chapter house which was begun in 1288, with carved capitals representing different species of plants. To clarify, Minster is an honorific title given to particular churches in England, most notably York Minster in Yorkshire, Westminster Abbey in London and Southwell Minster here in Nottinghamshire.The term ‘minster’ is first found in royal foundation charters of the seventh century, when it designated any settlement of clergy living a communal life and endowed by charter with the obligation of maintaining the daily office of prayer. Widespread in tenth-century England, minsters declined in importance with the systematic introduction of parishes and parish churches from the eleventh century onwards. The term continued as a title of dignity in later medieval England, for instances where a cathedral, monastery, collegiate church or parish church had originated with an Anglo-Saxon foundation. Eventually a minster came to refer more generally to “any large or important church, especially a collegiate or cathedral church”. In the twenty-first century, the Church of England has designated additional minsters by bestowing the status on certain parish churches, the most recent elevation to minster status being St Mary Magdalene church in Taunton, Somerset on 13 March 2022, bringing the total number of current Church of England minsters to thirty-one. As for Southwell, the earliest church on the site is believed to have been founded in 627AD by Paulinus, the first Archbishop of York, when he visited the area whilst baptising believers in the River Trent. The legend is actually commemorated in the Minster’s baptistry window. In 956AD King Eadwig gave land in Southwell to Oskytel, Archbishop of York, on which a minster church was established. The Domesday Book of 1086 recorded the Southwell manor in great detail. The Norman reconstruction of the church began in 1108, probably as a rebuilding of the Anglo-Saxon church, starting at the east end so that the high altar could be used as soon as possible and the Saxon building was dismantled as work progressed. Many stones from this earlier Anglo-Saxon church were reused in the construction. The tessellated floor and late eleventh century tympanum in the north transept are the only parts of the Anglo-Saxon building remaining intact. Work on the nave began after 1120 and the church was completed by c.1150. The church was originally attached to the Archbishop of York’s Palace which stood next door but is now ruined. It served the archbishop as a place of worship and was a collegiate body of theological learning, hence its designation as a minster. The minster draws its choir from the nearby school with which it is associated. In my research I found a comment saying that the Norman chancel was square-ended, but I can find no relevance to this elsewhere. The chancel was replaced with another in the Early English style in 1234–51 because it was too small. The octagonal chapter house, built starting in 1288 with a vault in the Decorated Gothic style has naturalistic carvings of foliage. The elaborately carved ‘pulpitum’ or choir screen was built in 1320–40. The church suffered less than many others during the English Reformation as it was re-founded in 1543 by Act of Parliament. Southwell is where King Charles I surrendered to Scottish Presbyterian troops in 1646 during the English Civil War, after the third siege of Newark. The fighting saw the church seriously damaged and the nave is said to have been used as stabling. The adjoining palace was almost completely destroyed, first by Scottish troops and then by the local people, with only the Hall of the Archbishop remaining as a ruined shell. Then on 5 November 1711 the southwest spire was struck by lightning, and the resulting fire spread to the nave, crossing and tower destroying roofs, bells, clock and the organ. By 1720 repairs had been completed, now giving a flat panelled ceiling to the nave and transepts. In 1805, Archdeacon Kaye gave the Minster the Newstead lectern which was once owned by Newstead Abbey. It had been thrown into the abbey fishpond by the monks to save it during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, then later discovered when the lake was dredged! Then in 1818, Henry Gally Knight gave the Minster four panels of sixteenth century Flemish glass (which now fill the bottom part of the East window) which he had acquired from a Parisian pawnshop. In 1805 the spires were found to be in danger of collapse, they were re-erected in 1879–81 when the minster was extensively restored by Ewan Christian, an architect specialising in churches. The nave roof was replaced with a pitched roof and the quire was redesigned and refitted.

The whole place has quite an ecclesiastical history, and Southwell Minster was served by prebendaries from the early days of its foundation. By 1291 there were sixteen Prebends of Southwell mentioned in the Taxation Roll. In August 1540, as the dissolution of the monasteries was coming to an end, and despite its collegiate rather than monastic status, Southwell Minster was suppressed specifically in order that it could be included in the plans initiated by King Henry VIII to create several new cathedrals. It appears to have been proposed as the see for a new diocese comprising both Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire as a replacement for Welbeck Abbey which had been dissolved in 1538 and which by 1540 was no longer owned by the Crown. The plan for the minster’s elevation did not proceed, so in 1543 Parliament reconstituted its collegiate status as before. In 1548 it again lost its collegiate status under the 1547 Act of King Edward VI which suppressed, amongst others, almost all collegiate churches. At Southwell, the prebendaries were given pensions and the estates sold, whilst the church continued as the parish church on the petitions of the parishioners. By an Act of Philip and Mary in 1557, the minster and its prebends were restored and in 1579 a set of statutes was promulgated by Queen Elizabeth I. The chapter operated under this constitution until it was dissolved in 1841. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners made provision for the abolition of the chapter as a whole such that the death of each canon after this time resulted in the extinction of his prebend. The chapter came to its appointed end on 12 February 1873 with the death of Thomas Henry Shepherd, rector of Clayworth and prebendary of Beckingham. Despite the plans to make Southwell Minster a cathedral in August 1540 not initially coming to fruition, 344 years later in 1884 Southwell Minster became a cathedral proper for Nottinghamshire and a part of Derbyshire including the city of Derby. In 1927 the diocese was divided and the Diocese of Derby was formed.

Architecturally, the nave, transepts, central tower and two western towers of the Norman church which replaced the Anglo-Saxon minster remain as an outstanding achievement of severe Romanesque design. With the exception of fragments mentioned above, they are the oldest part of the existing church.

The nave is of seven bays, plus a separated western bay. The columns of the arcade are short and circular, with small scalloped capitals. The triforium has a single large arch in each bay and the clerestory has small round-headed windows whilst the external window openings are circular. There is a tunnel-vaulted passage between the inside and outside window openings of the clerestory, the nave aisles are vaulted, the main roof of the nave is a trussed rafter roof, with tie-beams between each bay, these being a late nineteenth century replacement. By contrast with the nave arcade, the arches of the crossing are tall, rising to nearly the full height of the nave walls. The capitals of the east crossing piers depict scenes from the life of Jesus. Two stages of the inside of the central tower can be seen at the crossing, with cable and wave decoration on the lower order and zigzag on the upper. The transepts have three stories with semi-circular arches, like the nave, but without aisles.

The western facade has pyramidal spires on its towers – a unique feature today, though common in the twelfth century. The existing spires date only from 1880, but they replace those destroyed by fire in 1711, which are documented in old illustrations. The large west window dates from the fifteenth century. The central tower’s two ornamental stages place it high among England’s surviving Norman towers and whilst the lower order has intersecting arches, the upper order has plain arches. The north porch has a tunnel vault, and is decorated with intersecting arches. The choir is Early English in style, and was completed in 1241 and it has transepts, thus separating the choir into a western and eastern arm. The choir is of two storeys, with no gallery or triforium. The lower storey has clustered columns with multiform pointed arches, the upper storey has twin lancet arches in each bay. The rib vault of the choir springs from clustered shafts which rest on corbels. The vault has ridge ribs. The square east end of the choir has two stories each of four lancet windows.

In the 14th century the chapter house and the choir screen were added. The chapter house, started in 1288, is in an early decorated style, octagonal, with no central pier. It is reached from the choir by a passage and vestibule, through an entrance portal. This portal has five orders, and is divided by a central shaft into two subsidiary arches with a circle with quatrefoil above. Inside the chapter house, the stalls fill the octagonal wall sections, each separated by a single shaft with a triangular canopy above. The windows are of three lights, above them two circles with trefoils and above that a single circle with quatrefoil. This straightforward description gives no indication of the glorious impression, noted by so many writers, of the elegant proportions of the space, and of the profusion (in vestibule and passage, not just in the chapter house) of exquisitely carved capitals and tympana, mostly representing leaves in a highly naturalistic and detailed representation. The capitals in particular are deeply undercut, adding to the feeling of realism. Individual plant species such as ivy, maple, oak, hop, hawthorn can often be identified. The rood screen dates from 1320 to 1340, and is an outstanding example of the Decorated style. It has an east and west facade, separated by a vaulted space with flying ribs. The east facade, of two storeys, is particularly richly decorated, with niches on the lower storey with ogee arches, and openwork gables on the upper storey. The central archway rises higher than the lower storey, with an ogee arch surmounted by a cusped gable. The finest memorial in the minster is the alabaster tomb of Edwin Sandys, Archbishop of York, who died in 1588. As for choirs, the Cathedral Choir comprises the boy choristers, girl choristers, and lay clerks who, between them, provide music for seven choral services each week during school terms. The boys and girl choristers usually sing as separate groups, combining for particularly important occasions such as Christmas and Easter services, and notable events in the life of the minster. Regular concerts and international tours are a feature of the choir’s work. Services have been sung in Southwell Minster for centuries, and the tradition of daily choral worship continues to thrive. There was originally a college of vicars choral who took the lead as singers, one or two of whom were known as ‘rector chori’, or ‘ruler of the choir’. The vicars choral lived in accommodation where Vicars Court now stands, and lived a collegiate lifestyle.The current Cathedral Choir owes its form to the addition of boy choristers to the vicars choral, and the vicars themselves eventually being replaced by lay singers, known as lay clerks. For a large period of time, the format remained very similar, with a number of boy choristers singing with a mixture of lay clerks and vicars choral, slowly becoming a group of entirely lay singers. Eventually, in 2005, a girls’ choir was started by the Assistant Director of Music, who have now been formally admitted as girl choristers. All of the choristers are educated at the Minster School, a Church of England academy with a music-specialist Junior Department (years 3–6) for choristers and other talented young musicians. The Cathedral Choir has an enviable reputation for excellence, and has recorded and broadcast extensively over the years. Regular concerts and international tours are a feature of the choir’s work, alongside more local events such as civic services and the annual Four Choirs’ Evensong together with the cathedral choirs of Derby, Leicester and Coventry.

The Cathedral Choir can be heard singing at evensongs at 5.30 pm every weekday (except Wednesday), and on Saturdays and Sundays. In addition, there is ‘The Minster Chorale’, which is Southwell Minster’s auditioned adult voluntary choir, and is directed by the Minster’s Assistant Director of Music, Jonathan Allsopp. Founded in 1994, the Chorale’s purpose is to regularly sing for services, especially at times when the Cathedral Choir is not available. In particular, the Chorale sings for a mixture of services throughout the year. In addition to its regular round of services, one of the highlights of the Chorale’s year is its annual performance of Handel’s Messiah in the run-up to Christmas and this concert is a staple of the Minster’s Christmas programme, so is always packed out. The Chorale also regularly goes on tour, in recent years they have toured to the Channel Islands and the Scilly Isles. A 2020 tour to Schwerin, Germany was planned (together with Lincoln Cathedral Consort), but this was cancelled due to the Coronavirus pandemic. The Chorale also visits other cathedrals to sing services, and recently has been to York Minster. Southwell Minster Chorale rehearses weekly during term-time on a Friday from 7:45 pm – 9:15 pm. The Chorale also enjoys a good social life, with regular trips to the pub after rehearsals and for Sunday lunches.The minster is also home to the annual Southwell Music Festival, held in late August. However, as previously mentioned, many years ago I was able to sing the services as part of a visiting choir. We were small in number, so I had to sing up a bit – but we managed!

To end with, I have found a couple of old illustrations.

This week… Dictators.

“Speaking openly about dictators is like stepping on the tail of a snake. Do so and it will turn and bite you. To kill it, you must chop off its head.” ~ Author unknown.

Click: Return to top of page or Index page