A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. The art of tattooing has been practiced across the globe since at least Neolithic times, as evidenced by mummified preserved skin, ancient art and the archaeological record. Both ancient art and archaeological finds of possible tattoo tools suggest tattooing was practiced by the Upper Paleolithic period in Europe, however direct evidence for tattooing on mummified human skin extends only to the fourth millennium BC. The oldest discovery of tattooed human skin to date has been found on the body of Ötzi the Iceman, dating to between 3370 and 3100 BC. Other tattooed mummies have been recovered from many archaeological sites, including locations in Greenland, Alaska, Siberia, Mongolia, western China, Egypt, Sudan, the Philippines and the Andes. There are preserved tattoos on ancient mummified human remains which reveal that tattooing has been practiced throughout the world for millennia. In 2015, scientific re-assessment of the age of the two oldest known tattooed mummies identified as the oldest example then known. This body, with sixty-one tattoos, was found embedded in glacial ice in the Alps and was dated to 3250 BC. In 2018 the oldest figurative tattoos in the world were discovered on two mummies from Egypt which are dated between 3351 and 3017 BC.

Ancient tattooing was widely practiced among the Austronesian people and was one of the early technologies developed by the pre-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China prior to at least 1500 BC, before the Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific. For the most part, Austronesians used characteristic perpendicularly hafted tattooing points that were tapped on the handle with a length of wood to drive the tattooing points into the skin. The handle and mallet were generally made of wood whilst the points, either single, grouped or arranged to form a comb were made of Citrus thorns, fish bone, bone, teeth and turtle and oyster shells.

Cemeteries throughout the Tarim Basin of western China have revealed several tattooed mummies with Western Asian/Indo-European physical traits and cultural materials. These date from between 2100 and 550 BC. In ancient China, tattoos were considered a barbaric practice associated with the Yue peoples of southeastern and southern China. Tattoos were often referred to in literature depicting bandits and folk heroes. As late as the Qing dynasty it was common practice to tattoo characters such as ‘Prisoner’ on convicted criminals’ faces. Although relatively rare during most periods of Chinese history, slaves were also sometimes marked to display ownership. However, tattoos seem to have remained a part of southern culture. Marco Polo wrote that “Many come hither from Upper India to have their bodies painted with the needle in the way we have elsewhere described, there being many adepts at this craft in the city”. The Indigenous peoples of North America have a long history of tattooing. Tattooing was not a simple marking on the skin: it was a process that highlighted cultural connections to Indigenous ways of knowing and viewing the world, as well as connections to family, society, and place. There has been no way to determine the actual origin of tattooing for these people, though it is known that the St. Lawrence Iroquoians had used bones as tattooing needles, and turkey bone tattooing tools were discovered at an ancient Fernvale, Tennessee site, dated back to 3500–1600 BC. Until recently, archeologists have not prioritised the classification of tattoo implements when excavating known historic sites, but recent review of materials found from one excavation site point towards elements of tattoo bundles that are from pre-colonisation times. Scholars explain that the recognition of tattoo implements is significant because it highlights the cultural importance of tattooing for indigenous people.

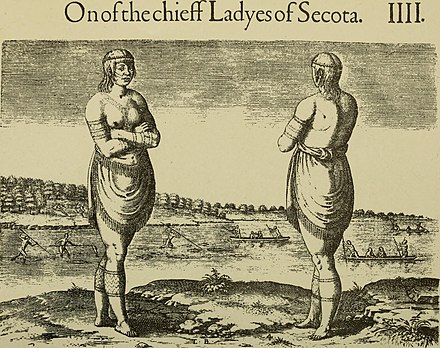

The above is a page from Thomas Harriot’s book ‘A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia’ showing a painting by John White. Markings on the skin represent tattoos that were observed. Early explorers to North America made many ethnographic observations about the people they met. Initially, they did not have a word for tattooing and instead described these modifications as to ‘’stamp, paint, burn, and embroider’ the skin. The Jesuit Relations of 1652 describes tattooing as “But those who paint themselves permanently do so with extreme pain, using, for this purpose, needles, sharp awls, or piercing thorns, with which they perforate, or have others perforate, the skin. Thus they form on the face, the neck, the breast, or some other part of the body, some animal or monster, for instance, an Eagle, a Serpent, a Dragon, or any other figure which they prefer; and then, tracing over the fresh and bloody design some powdered charcoal, or other black colouring matter, which becomes mixed with the blood and penetrates within these perforations, they imprint indelibly upon the living skin the designed figures. And this in some nations is so common that in the one which we called the Tobacco, and in that which – on account of enjoying peace with the Hurons and with the Iroquois – was called Neutral, I know not whether a single individual was found, who was not painted in this manner, on some part of the body”. It seems that the Inuit also have a deep history of tattooing. In the Inuit language of the eastern Canadian Arctic, the word ‘kakiniit’ translates to the English word for tattoo and the word ‘tunniit’ means face tattoo. Among the Inuit, some tattooed female faces and parts of the body symbolise a girl transitioning into a woman, coinciding with the start of her first menstrual cycle. A tattoo represented a woman’s beauty, strength, and maturity, and this was an important practice because some Inuit believed that a woman could not transition into the spirit world without tattoos on her skin. But European missionaries colonised the Inuit in the beginning of the twentieth century and associated tattooing as an evil practice, ‘demonizing’ anyone who valued tattoos. But latterly people have talked to elder Inuit folk and these elders were able to recall the traditional practice of tattooing, which often included using a needle and thread and sewing the tattoo into the skin by dipping the thread in soot or seal oil, or through skin poking using a sharp needle point and dipping it into soot or seal oil. As a result, work has been done with the elders in their community to bring the tradition of kakiniit back by learning the traditional ways of tattooing and using their skills to tattoo others. However the Osage people, a Mid-western Native American tribe of the Great Plains used tattooing for a variety of different reasons. The tattoo designs were based on the belief that people were part of the larger cycle of life and integrated elements of the land, sky, water, and the space in between to symbolise these beliefs. These people also believed in the smaller cycle of life, recognising the importance of women giving life through childbirth and men removing life through warfare. Osage men were often tattooed after accomplishing major feats in battle, as a visual and physical reminder of their elevated status in their community. Some Osage women were tattooed in public as a form of a prayer, demonstrating strength and dedication to their nation. Meanwhile in central America a Spanish expedition led by Gonzalo de Badajoz in 1515 across what is today Panama ran into a village where prisoners from other tribes had been marked with tattoos. Except the Spaniards did find some slaves who were branded in a painful fashion. The natives cut lines in the faces of the slaves, using a sharp point either of gold or of a thorn; they then fill the wounds with a kind of powder dampened with black or red juice, which forms an indelible dye and never disappears.

Tattooing for spiritual and decorative purposes in Japan is thought to extend back to at least the Jomon or Paleolithic period and was widespread during various periods for both the Yamato and native Jomon groups. Chinese texts from before 300 AD described social differences among Japanese people as being indicated through tattooing and other bodily markings. Chinese texts from the time also described Japanese men of all ages as decorating their faces and bodies with tattoos. Generally firemen, manual workers and prostitutes wore tattoos to communicate their status, but by the early seventeenth century, criminals were widely being tattooed as a visible mark of punishment. Criminals were marked with symbols typically including crosses, lines, double lines and circles on certain parts of the body, mostly the face and arms. These symbols sometimes designated the places where the crimes were committed. In one area, the character for “dog” was tattooed on the criminal’s forehead. Then the Government of Meiji, formed in 1868, banned the art of tattooing altogether, viewing it as barbaric and lacking respectability. This subsequently created a subculture of criminals and outcasts. These people had no place in ‘decent’ society and were frowned upon. They could not simply integrate into mainstream society because of their obvious visible tattoos, forcing many of them into criminal activities which ultimately formed the roots for the modern Japanese mafia, the Yakuza, with which tattoos have become almost synonymous in Japan. It seems too that Thai-Khmer tattoos, also known as Yantra tattooing, was common since ancient times. Just as other native southeast Asian cultures, animistic tattooing was common in Tai tribes that were is southern China. Over time, this animistic practice of tattooing for luck and protection assimilated Hindu and Buddhist ideas. The Sak Yant traditional tattoo is practiced today by many and are usually given either by a Buddhist monk or a Brahmin priest. The tattoos usually depict Hindu gods and used different scripts which were the scripts of the classical civilisations of mainland southeast Asia.

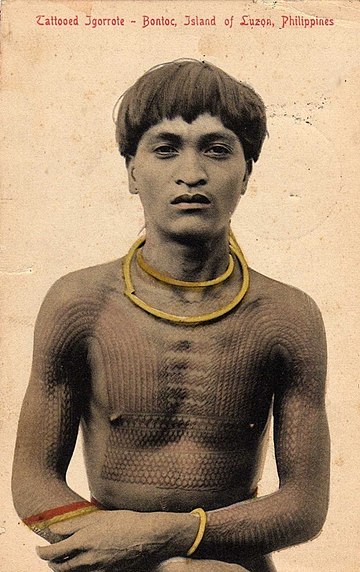

Tattooing, or ‘batok’ on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era. Ancient clay human figurines found in archaeological sites in the Batanes Islands, around 2500 to 3000 years old, have simplified stamped-circle patterns, which are believed to represent tattoos and possibly branding (also commonly practiced) as well. Excavations at the Arku Cave burial site in Cagayan Province in northern Luzon have also yielded both chisel and serrated-type heads of possible hafted bone tattoo instruments alongside Austronesian material culture markers like adzes, spindle whorls, bark-cloth beaters, and jade ornaments. These were dated to before 1500 BC and are remarkably similar to the comb-type tattoo chisels found throughout Polynesia. Tattoos are acquired gradually over the years, and patterns can take months to complete and heal. For many the tattooing processes are sacred events that involve rituals to ancestral spirits and the heeding of omens. For example, if the artist or the recipient sneezes before a tattooing, it was seen as a sign of disapproval by the spirits, and the session was called off or rescheduled. At one time artists were usually paid with livestock, heirloom beads, or precious metals. They were also housed and fed by the family of the recipient during the process. A celebration was usually held after a completed tattoo. The Māori people of New Zealand practised a form of tattooing known as ‘tā moko’, traditionally created with chisels. However, from the late twentieth century onwards, there has been a resurgence of tā moko taking on European styles amongst Maori. Traditional tā moko was reserved for head area. There is also a related tattoo art, kirituhi, which has a similar aesthetic to tā moko but is worn by non-Maori.

The earliest possible evidence for tattooing in Europe appears on ancient art from the Upper Paleolithic period as incised designs on the bodies of humanoid figurines. The Löwenmensch figurine from the Aurignacian culture dates to approximately 40,000 years ago and features a series of parallel lines on its left shoulder. The ivory ‘Venus of Hohle Fels’, which dates to between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago also exhibits incised lines down both arms, as well as across the torso and chest. The Picts may have been tattooed with elaborate, war-inspired black or dark blue woad designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his ‘Gallic Wars’ (54 BC). Nevertheless, these may have been painted markings rather than tattoos. Raised in the aftermath of the Norman conquest of England, William of Malmesbury describes in his ‘Gesta Regum Anglorum’ that the Anglo-Saxons were tattooed upon the arrival of the Normans as ‘arms covered with golden bracelets, tattooed with coloured patterns’. The significance of tattooing was long open to Eurocentric interpretations. In the mid-nineteenth century, Baron Haussmann, whilst arguing against painting the interior of Parisian churches, said the practice “reminds me of the tattoos used in place of clothes by barbarous peoples to conceal their nakedness”. Meanwhile Greek written records of tattooing date back to at least the fifth-century BC. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans used tattooing to penalise slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war. However, in Egypt and Syria, known decorative tattooing was looked down upon and only religious tattooing was mainly practiced. In 316, emperor Constantine I made it illegal to tattoo the face of slaves as punishment. The Greek verb ‘stizein’, meaning ‘to prick’, was used for tattooing. Its derivative ‘stigma’ was the common term for tattoo marks in both Greek and Latin. It still fascinates me how our ‘modern’ words originated! During the Byzantine period, the verb ‘kentein’ replaced ‘stizein’, and a variety of new Latin terms replaced ‘stigmata’ including ‘signa’ or “signs”, ‘characteres’ or “stamps,” and ‘cicatrices’ or “scars”.

Despite a lack of direct textual references, tattooed human remains and iconographic evidence indicate that ancient Egyptians practiced tattooing from at least 2000 BC. It is theorised that tattooing entered Egypt through Nubia, but this claim is complicated by the high mobility between Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt as well as Egypt’s annexation of Lower Nubia around 2000 BC and one archeologist has argued that it may be more appropriate to classify tattoo in ancient Egypt and Nubia as part of a larger Nile Valley tradition. Ancient Egyptian tattooing appears to have been practiced on women exclusively; with an exception of a pre-dynastic male mummy found with “Dark smudges on his arm, appearing as faint markings under natural light, had remained unexamined. Infrared photography recently revealed that these smudges were in fact tattoos of two slightly overlapping horned animals. The horned animals have been tentatively identified as a wild bull (long tail, elaborate horns) and a Barbary sheep (curving horns, humped shoulder). Both animals are well known in Predynastic Egyptian art. The designs are not superficial and have been applied to the dermis layer of the skin, the pigment was carbon-based, possibly some kind of soot.” Two well-preserved Egyptian mummies from 4160 BC, a priestess and a temple dancer for the fertility goddess Hathor, bear random-dot and dash tattoo patterns on the lower abdomen, thighs, arms, and chest.

Meanwhile British and other pilgrims to the Holy Lands throughout the seventeenth century were tattooed with the Jerusalem Cross to commemorate their voyages. Between 1766 and 1779, Captain James Cook made three voyages to the South Pacific, the last trip ending with Cook’s death in Hawaii in February 1779. When Cook and his men returned home to Europe from their voyages to Polynesia, they told tales of the ‘tattooed savages’ they had seen. The word “tattoo” itself comes from the Tahitian word ‘tatau’, and was introduced into the English language by Cook’s expedition, though the word ‘tattoo’ or ‘tap-too’, referring to a drumbeat, had existed in English since at least 1644. It was in Tahiti aboard the Endeavour, in July 1769, that Cook first noted his observations about the indigenous body modification and is the first recorded use of the word tattoo to refer to the permanent marking of the skin. In the ship’s log book recorded this entry: “Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible.” Cook went on to write, “This method of Tattowing I shall now describe…As this is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their Buttocks, it is performed but once in their Lifetimes.” Cook’s Science Officer and Expedition Botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, returned to England with a tattoo. Banks was a highly regarded member of the English aristocracy and had acquired his position with Cook by putting up what was at the time the princely sum of some ten thousand pounds in the expedition. In turn, Cook brought back with him a tattooed Raiatean man, Omai, who he presented to King George and the English Court. Many of Cook’s men, ordinary seamen and sailors, came back with tattoos, a tradition that would soon become associated with men of the sea in the public’s mind and the press of the day. In the process, sailors and seamen re-introduced the practice of tattooing in Europe, and it spread rapidly to seaports around the globe. By the nineteenth century, tattooing had spread to British society but was still largely associated with sailors and the lower or even criminal class. Tattooing had however been practiced in an amateur way by public schoolboys from at least the 1840s and by the 1870s had become fashionable among some members of the upper classes, including royalty. In its ‘upmarket’ form, it could be a lengthy, expensive and sometimes painful process. Tattooing spread among the upper classes all over Europe in the nineteeenth century, but particularly in Britain where it was estimated in Harmsworth Magazine in 1898 that as many as one in five members of the gentry were tattooed. Taking their lead from the British Court, where King George V followed King Edward VII’s lead in getting tattooed; King Frederick IX of Denmark, the King of Romania, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alexander of Yugoslavia and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia all sported tattoos, many of them elaborate and ornate renditions of the Royal Coat of Arms or the Royal Family Crest. King Alfonso XIII of modern Spain also had a tattoo. The perception that there is a marked class division on the acceptability of the practice has been a popular media theme in Britain, as successive generations of journalists described the practice as newly fashionable and no longer for a marginalised class. Examples of this cliché can be found in every decade since the 1870s. Despite this evidence, a myth persists that the upper and lower classes find tattooing attractive and the broader middle classes rejecting it.

As World War I ravaged the globe, it also ravaged the popularity of tattooing, pushing tattoos even farther under the umbrella of delinquency. What credence tattoos got as symbols of patriotism and war badges in the eyes of the public, was demolished as servicemen moved away from the proud flags motifs and into more sordid depictions. At the beginning ofWorld War II, tattooing once again experienced a boom in popularity as now not only sailors in the Navy, but soldiers in the Army and fliers in the Air Force, were once again tattooing their national pride onto their bodies. During the Second World War, the Nazis, under the order of Adolph Hitler, rounded up those deemed inferior into concentration camps. Once there, if they were chosen to live, they were tattooed with numbers onto their arms. Tattoos and Nazism become intertwined, and the extreme distaste for Nazi Germany and Fascism led to a stronger public outcry against tattooing. This backlash would further worsen with use of a tattooed man in a 1950s Marlboro advertisement, which strengthened the public’s view that tattoos were no longer for patriotic servicemen, but for criminals and degenerates. The public distaste was so strong by this point, that usual trend of seeing tattoo popularity spike during times of war, was not seen in the Vietnam War. It would take two more decades for tattooing to finally be brought back into society’s good graces. Interestingly, throughout the world’s different military branches, tattoos are either regulated under policies or strictly prohibited to fit dress code rules. In the United Kingdom, as of 2022 the Royal Navy permits most tattoos, with certain restrictions: unless visible in a front-facing passport photo, obscene or offensive, or otherwise deemed inappropriate. The National Museum of the Royal Navy has presented an exhibit about the long history of tattoos among Navy service members, part of the tradition of sailor tattoos. In the United States, the United States Air Force regulates all kinds of body modification. Any tattoos which are deemed to be “prejudicial to good order and discipline”, or “of a nature that may bring discredit upon the Air Force” are prohibited. Specifically, any tattoo which may be construed as “obscene or advocate sexual, racial, ethnic or religious discrimination” is disallowed. Tattoo removal may not be enough to qualify; resultant “excessive scarring” may be disqualifying. Further, Air Force members may not have tattoos on their neck, face, head, tongue, lips or scalp. The United States Army permits soldiers to have tattoos as long as they are not on the neck, hands, or face, with exceptions existing for of one ring tattoo on each hand and permanent makeup. Additionally, tattoos that are deemed to be sexist, racist, derogatory, or extremist continue to be banned and the United States Navy has changed its policies and become more lenient on tattoos, allowing neck tattoos as long as one inch. Sailors are also allowed to have as many tattoos of any size on the arms and legs, as long as they are not deemed to be offensive tattoos. I have also found that the Indian Army tattoo policy has been in place since 11 May 2015. The government declared all tribal communities who enlist and have tattoos are allowed to have them all over the body only if they belong to a tribal community. Indians who are not part of a tribal community are only allowed to have tattoos in designated parts of the body such as the forearm, elbow, wrist, the side of the palm, and back and front of hands. Offensive, sexist and racist tattoos are not allowed. I have learned too that tattooing in the federal Indian boarding school system was commonly practiced during the 1960s and 1970s. Such tattoos often took the form of small markings or initials and were often used as a form of resistance; a way to reclaim one’s body. Due to the forced assimilation practices of the Western boarding schools, many indigenous cultural practices were on a severe decline, tattooing being one of them. As a way to retain their cultural heritage some students practiced this ritual and tattooed themselves with found materials like sewing needles and India Ink. Within the schools, the authorities physically labeled the students: “a personal identification number was written in purple ink on their wrists and on the small cupboard in which their few belongings were stored.” Students often had a tendency to tattoo their initials on this very spot; the exact place where the school authorities first marked them. This can be seen as a strong act of resistance where the students were physically rejecting their numerical ID, and reclaiming their own body and identity. Here in the United Kingdom, in 1969 the House of Lords debated a bill to ban the tattooing of minors, on grounds it had become “trendy” with the young in recent years but was associated with crime. It was noted that forty per cent of young criminals had tattoos and that marking the skin in this way tended to encourage self-identification with criminal groups. Since the 1970s, tattoos have become more socially acceptable and fashionable among celebrities. Tattoos are less prominent on figures of authority, and the practice of tattooing by the elderly is still considered remarkable. In recent history, authority figures have adopted the trend more widely; in Australia 65% of people in these professions are tattooed. Tattooing has also steadily increased in popularity since the invention of the electric tattoo machine. In 1936, 1 in 10 Americans had a tattoo of some form. Since the 1970s, tattoos have become a mainstream part of global and Western fashion, common among both sexes, to all economic classes, and to age groups from the later teen years to middle age. Tattoos have experienced a resurgence in popularity in many parts of the world, particularly in Europe, Japan, and North and South America. The growth in tattoo culture has seen an influx of new artists into the industry, many of whom have technical and fine arts training. Coupled with advancements in tattoo pigments and the ongoing refinement of the equipment used for tattooing, this has led to an improvement in the quality of tattoos being produced. Over the past three decades Western tattooing has become a practice that has crossed social boundaries from “low” to “high” class along with reshaping the power dynamics regarding gender. But it has its roots in “exotic” tribal practices of the Native Americans and Japanese, which are still seen in present times.

This week… thoughts.

If electricity comes from electrons, does morality come from morons?

A hangover is the wrath of grapes.

Click: Return to top of page or Index page