An official description of writing is “a cognitive and social activity involving involving neuropsychological and physical processes and the use of writing systems to structure and translate human thoughts into persistent representations of human language”. A system of writing relies on many of the same semantic structures as the language it represents, such as lexicon and syntax, with the added dependency of a system of symbols representing that language’s phonology and morphology. Nevertheless, a written language may take on characteristics distinctive from any available in spoken language. The outcome of this activity, sometimes referred to as ‘text’, is a series of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred or digitally represented linguistic symbols. The interpreter or activator of a text is called a ‘reader’. Writing systems do not themselves constitute languages, with the debatable exception of computer languages, they are a means of rendering language into a form that can be read and reconstructed by other humans separated by time and/or space. Whilst not all languages use a writing system, those that do can complement and extend the capacities of spoken language by creating durable forms of language that can be transmitted across space, for example written correspondence, and stored over time in such places as libraries or other public records. Writing can also have knowledge-transforming effects, since it allows humans to externalise their thinking in forms that are easier to reflect on, elaborate on, reconsider, and revise. Any instance of writing involves a complex interaction amongst available tools, intentions, cultural customs, cognitive routines, genres, tacit and explicit knowledge, and the constraints and limitations of the writing system(s) deployed. Over time, inscriptions have been made with fingers, styluses, quills, ink brushes, pencils, pens and many styles of lithography. The surfaces used for these inscriptions have included stone tablets, clay tablets, bamboo slats, papyrus, wax tablets, vellum, parchment, paper, copperplate, slate, porcelain and other enamelled surfaces. The Incas used knotted cords known as quipu (or khipu) for keeping records. Writing tools and surfaces have been countlessly improvised throughout history, as the cases of graffiti, tattooing and impromptu aides-memoire illustrate. In fact I believe tattoos were put on sailors so that they could be identified more easily after their deaths.

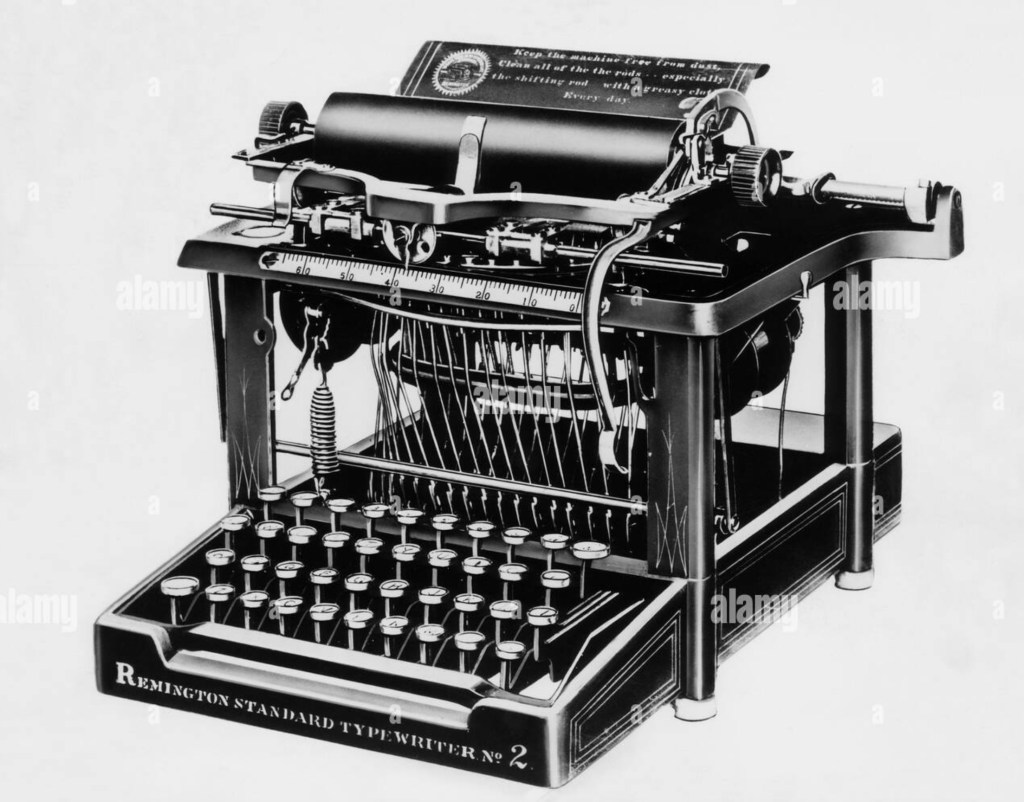

The typewriter and subsequently various digital word processors have recently become widespread writing tools, and studies have compared the ways in which writers have framed the experience of writing with such tools as compared with the pen or pencil. Advancements in technology have allowed certain tools in the form of software to produce better and better text editing, although human input is vital to prevent simple errors from creeping in! However, writing technologies from different eras coexist easily in many homes and workplaces. During the course of a day or even a single episode of writing, for example, a writer might instinctively switch between a pencil, a touchscreen, a text-editor, a whiteboard, a legal pad, and adhesive notes as different purposes arise. Nowadays so many of us learn to read and write as part of our upbringing and schooling, but it wasn’t always so. As human societies emerged, collective motivations for the development of writing were driven by pragmatic exigencies like keeping track of produce and other wealth, recording history, maintaining culture, codifying knowledge through curricula and lists of texts deemed to contain foundational knowledge, organising and governing societies through the formation of legal systems, census records, contracts, deeds of ownership, taxation, trade agreements, treaties, and so on. Around the fourth millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory and writing became a more dependable method for the permanent recording and presentation of transactions. Writing may have also evolved through calendric and political necessities for recording historical and environmental events. Further innovations included more uniform, predictable, and widely dispersed legal systems, the distribution of accessible versions of sacred texts and furthering practices of scientific inquiry and knowledge consolidation, all of which were largely reliant on portable and easily reproducible forms of inscribed language. In addition, the nearly global spread of digital communication systems such as e-mail and social media has made writing an increasingly important feature of daily life, where these systems mix with older technologies like paper, pencils, whiteboards, printers, and copiers. Substantial amounts of everyday writing characterise most workplaces in developed countries and in many occupations written documentation is not only the main deliverable but also the mode of work itself. Even in occupations not typically associated with writing, routine workflows have most employees writing at least some of the time.

Some professions are typically associated with writing, such as literary authors, journalists, and technical writers, but writing is pervasive in most modern forms of work, civic participation, household management, and leisure activities. Whether it be through business and finance, governance and law, the production and sharing of scientific and scholarly knowledge, journalism, technical and medical writing, literature and the leisure book market or writing within education and educational institutions, formal education is the social context most strongly associated with the learning of writing, and students may carry these particular associations long after leaving school. Alongside the writing that students read in the forms of textbooks, assigned books, and other instructional materials as well as self-selected books, students do much writing within schools at all levels, on subject exams, in essays, in taking notes, in doing homework, and in formative as well as summative assessments. Some of this is explicitly directed toward the learning of writing, but much is focused more on subject learning. Students receive much writing from their teachers as well in the forms of assignments and syllabi, directions for activities, worksheets, corrections on work, or information about subjects or exams. Students also receive institutional notices and regulations, sometimes to be shared with families. Students may also write teacher evaluations for use by teachers to improve instruction or by others reviewing quality of teacher instruction, particularly within higher education. Writing also pervades schools and educational institutions in less visible and memorable ways. Since schools are typically hierarchically arranged bureaucracies, writing also circulates in the forms of notices and regulations that teachers receive from their supervisors and arrange their instruction according to district and state syllabi and regulations. Teachers must often produce and submit lesson plans or other information about their teaching. In primary and secondary education teachers may need to write notices or letters to parents about matters relating to their children’s learning, school activities, or regulations. Within school hierarchies many memos, notices, or other documents may flow. National policies and regulations as elaborated by ministries or departments of education may also be of consequence. Additionally, research in the various subject areas and in educational studies may be attended to by educators in the classroom and higher bureaucratic levels.

With the onset of computers has come computer programming in different languages and over the years these have become easier to follow. I myself learned simple computer language back in the 1980’s and used the knowledge quite effectively whilst at work. One language I learned is called BASIC, standing for Beginners All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code. Quite clever, I think. Because software development is the process of conceiving, specifying, designing, programming, documenting, testing and bug fixing involved in creating and maintaining applications, frameworks or other software components. And bugs do develop, most especially when several people are writing the programs. There is a great quote from Star Trek, where ’Scotty’ says “The more they overtake the plumbing, the easier it is to stop up the drain!”. It is true, because software development involves writing and maintaining the source code, but in a broader sense, it includes all processes from the conception of the desired software through the final manifestation, typically in a planned and structured process often overlapping with software engineering. Software development also includes research, new development, prototyping, modification, reuse, re-engineering, maintenance, or any other activities that result in software products. But it had to start somewhere and one way was using an alphabet, which is a set of written symbols that represent consonants and vowels. In a perfectly phonological alphabet, the letters would correspond perfectly to the language’s ‘phonemes’, these being any of the perceptually distinct units of sound in a specified language that distinguish one word from another, for example p, b, d, and t in the English words pad, pat, bad and bat. So a writer could predict the spelling of a word given its pronunciation, and a speaker could predict the pronunciation of a word given its spelling. However, as languages often evolve independently of their writing systems, and writing systems have been borrowed for languages they were not designed for, the degree to which letters of an alphabet correspond to phonemes of a language vary greatly from one language to another and even within a single language. Sometimes the term ‘alphabet’ is restricted to systems with separate letters for consonants and vowels, such as the Latin alphabet and because of this use, Greek is often considered to be the first language with an alphabet. In most of the alphabets of the Middle East, it is usually only the consonants of a word that are written, although vowels may be indicated by the addition of various diacritical marks. Writing systems based primarily on writing just consonants phonemes date back to the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt. Such systems are called ‘abjads’, derived from the Arabic word for alphabet. But in most of the alphabets of India and south-east Asia, vowels are indicated through diacritics or modification of the shape of the consonant and these are called ‘abugidas’. Some abugidas, such as Ethiopic and Cree, are learned by children as syllabaries, and so are often called ‘syllabics’. However, unlike true syllabaries, there is not an independent glyph for each syllable. There are also ‘Featural’ scripts, which represent the features of the phonemes of the language in consistent ways and an example of such a system is Korean hangul For instance, all labial sounds, ones pronounced with the lips, may have some element in common. In the Latin alphabet, this is accidentally the case with the letters “b” and “p”; however, labial “m” is completely dissimilar, and the similar-looking “q” and “d” are not labial. In the Korean hangul however, all four labial consonants are based on the same basic element, but in practice, Korean is learned by children as an ordinary alphabet, and the featural elements tend to pass unnoticed. Another featural script is SignWriting, the most popular writing system for many sign languages, where the shapes and movements of the hands and face are represented iconically. Such scripts are also common in fictional or invented systems.

The origins of writing are older than perhaps some may think though. For example, a stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing, known as the Cascajal Block, was discovered in the Mexican state of Veracruz and is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing by approximately 500 years and is thought to be Olmec who are the earliest known major Mesosmerican civilisation. Of the several pre-Columbian scripts that have been found in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed and to be really deciphered is the Maya script. The earliest inscription identified as Maya dates to the third century BC. This writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. In 2001, archaeologists discovered that there was a civilisation in Central Asia that used writing c. 2000 BC. An excavation near Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, revealed an inscription on a piece of stone that was used as a stamp seal. Meanwhile the earliest surviving examples of writing in China, inscriptions on so-called ‘oracle bones’, tortoise plastrons (the bony plate forming the ventral part of the shell of a tortoise or turtle) and ox scapulae, both used for divination, date from around 1200 BC in the late Shang dynasty. A small number of bronze inscriptions from the same period have also survived. In 2003, archaeologists reported discoveries of isolated tortoise-shell carvings dating back to the seventh millennium BC, but whether or not these symbols are related to the characters of the later oracle-bone script is disputed. This The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, is a significant Egyptian archaeological find, dating from about 3100 BC, belonging, at least nominally, to the category of cosmetic palettes. It contains some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever found. These hieroglyphs date back to the clay labels of a Predynastic ruler called ‘Scorpion I’ and were recovered at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa’ab) in 1998. There are also several recent discoveries that may be slightly older, though these glyphs were based on a much older artistic rather than written tradition. The hieroglyphic script was logographic with phonetic adjuncts that included an effective alphabet. The world’s oldest deciphered sentence was found on a seal impression found in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa’ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty, 28th or 27th century BC. There are around 800 hieroglyphs dating back to the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom Eras. By the Greco-Roman period, there were apparently more than 5,000. Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this apparently preserved the scribes’ status. The world’s oldest known alphabet appears to have been developed by Canaanite turquoise miners in the Sinai desert around the mid-nineteenth century BC. Around thirty crude inscriptions have been found at a mountainous Egyptian mining site known as Serabit el-Khadem. This site was also home to a temple of Hathor, the ‘Mistress of turquoise’. A later, two line inscription has also been found at Wadi el-Hol in Central Egypt. Based on hieroglyphic prototypes, but also including entirely new symbols, each sign apparently stood for a consonant rather than a word; the basis of an alphabetic system. It seems that it was not until the twelfth to ninth centuries, however, that the alphabet took hold and became widely used.

Over the centuries in Iran, three distinct Elamite scripts developed. Proto-Elamite is the oldest known writing system from there. In use only for a brief time (c. 3200–2900 BC), clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran, with the majority having been excavated at Susa, an ancient city located east of the Tigris and between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers. This Proto-Elamite script consists of more than 1,000 signs and is thought to be partly logographic. Meanwhile in Europe, notational signs from 37,000 years ago in caves, apparently convey calendaric meaning about the behaviour of animal species drawn next to them, and are considered the first known proto-writing in history. Hieroglyphs are found on artefacts of Crete from the early to mid-second millennium BC, and whilst the writing system of the Mycenaean Greeks has been deciphered, others have yet to be deciphered. In the Indus Valley, there is Indus script which refers to short strings of symbols associated with a civilisation there and which spanned modern-day Pakistan and North India used between 2600 and 1900 BC. In spite of many attempts at decipherments and claims, it is as yet undeciphered. The term ‘Indus script’ is mainly applied to that used in the mature Harappan phase, which perhaps evolved from a few signs found in early Harappa after 3500 BC, and was followed by the mature Harappan script. So, whilst research into the development of writing during the late Stone Age is ongoing, the current consensus is that it first evolved from economic necessity in the ancient Near East. Writing most likely began as a consequence of political expansion in ancient cultures, which needed reliable means for transmitting information, maintaining financial accounts, keeping historical records, and similar activities. Around the fourth millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration outgrew the power of memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form so the invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age of the late fourth millennium BC. It is generally agreed that Sumerian writing was an independent invention, however it is debated whether Egyptian writing was developed completely independently of Sumerian, or was a case of cultural diffusion.

In approximately 8000 BC, the Mesopotamians began using clay tokens to count their agricultural and manufactured goods. Later they began placing these tokens inside large, hollow clay containers (bulla, or globular envelopes) which were then sealed. The quantity of tokens in each container came to be expressed by impressing, on the container’s surface, one picture for each instance of the token inside. They next dispensed with the tokens, relying solely on symbols for the tokens, drawn on clay surfaces. To avoid making a picture for each instance of the same object (for example: 100 pictures of a hat to represent 100 hats), they ‘counted’ the objects by using various small marks. In this way the Sumerians added “a system for enumerating objects to their incipient system of symbols”. The original Mesopotamian writing system was derived around 3200 BC from this method of keeping accounts and by the end of the fourth millennium BC the Mesopotamians were using a triangular-shaped stylus pressed into soft clay to record numbers. This system was gradually augmented with using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted by means of pictographs. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus, at first only for logograms but later also for phonetic elements. Around 2700 BC, cuneiform began to represent syllables of spoken Sumerian. About that time, Mesopotamian cuneiform became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. This script was adapted to another Mesopotamian language, the East Semitic around 2600 BC, and then to others. With the adoption of Aramaic as the ‘lingua franca’ of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), Old Aramaic was also adapted to Mesopotamian cuneiform. The Phoenician writing system was adapted from the Proto-Canaanite script sometime before the fourteenth century BC, which in turn borrowed principles of representing phonetic information from Egyptian hieroglyphs. This writing system was an odd sort of syllabary in which only consonants are represented. This script was adapted by the Greeks, who adapted certain consonantal signs to represent their vowels. The Cumae alphabet, a variant of the early Greek alphabet, gave rise to the Etruscan alphabet and its own descendants, such as the Latin alphabet and Runes. Other descendants from the Greek alphabet include Cyrillic, used to write Bulgarian, Russian and Serbian, amongst others. The Phoenician system was also adapted into the Aramaic script, from which both Hebrew and Arabic scripts are descended.

But, in the history of writing, religious texts or writings have played a special role. For example, some religious text compilations have been some of the earliest popular texts, or even the only written texts in some languages, and in some cases are still highly popular around the world. The first books printed widely using the printing press were bibles. Such texts enabled rapid spread and maintenance of societal cohesion, collective identity, motivations, justifications and beliefs. Nowadays there are numerous programmes in place to aid both children and adults in improving their literacy skills. These resources, and many more, span across different age groups in order to offer each individual a better understanding of their language and how to express themselves via writing in order to perhaps improve their socio-economic status. One quote I like is “Did you ever notice that, when people become serious about communication, they want it in writing?”

This week… A few Yorkshire medical terms.

Artery – The study of paintings

Bacteria – Back door to cafeteria

Cauterise – Made eye contact with her

Click: Return to top of page or Index page